“ . . . Mary asked if I thought she resembled Mary Fuller. She had been told repeatedly that she did. There is a resemblance, but it is more striking in the pictures of the two Marys, as then their hair looks to be the same color. ‘I admire Mary Fuller very much. I’ve never met her, though I tried to on Edison night at the Exposition, but she had gone home.'” Mary Pickford, interviewed by Mabel Condon, “Sans Grease Paint and Wig,” Motography, August 23, 1913.

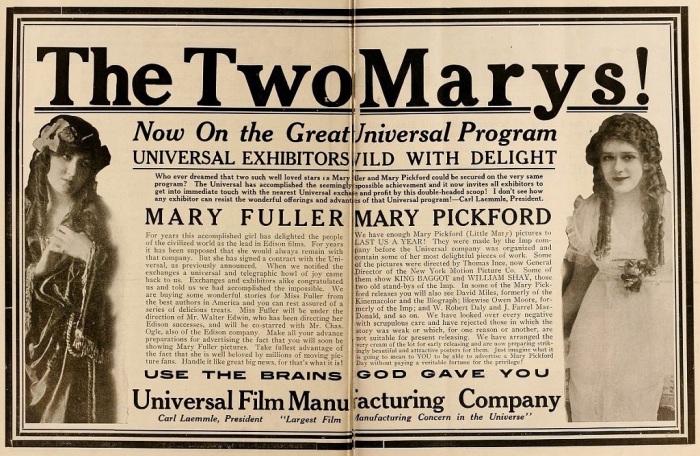

“Who ever dreamed that two such well loved stars as Mary Fuller and Mary Pickford could be secured on the very same program? The Universal has accomplished the seemingly impossible achievement and it now invites all exhibitors to get into immediate touch with the nearest Universal exchange and profit by this double-headed scoop! I don’t see how any exhibitor can resist the wonderful offerings and advantages of that Universal program!–Carl Laemmle, President” Ad for The Universal Picture Manufacturing Company, The Moving Picture World, July 18, 1914.

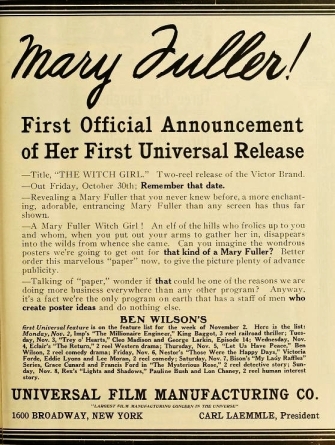

“USE THE BRAINS GOD GAVE YOU,” Carl Laemmle exhorted film exhibitors in this promotion of his apparent coup — offering on the same program the talents of two of the biggest names in the movies of 1914, Mary Pickford and Mary Fuller. Universal, the film production and distribution combination founded by Laemmle, had recently signed Fuller after she had been a star for his historic rival, Edison, for the past four years and had appeared in three groundbreaking, early movie serials the most recent of which, the twelve-part The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies, had concluded production in July.

Mary Pickford, however, was not an employee of Carl Laemmle, and hadn’t been since leaving his Independent Moving Pictures Company of America in late summer of 1911, after less than ten months with “The IMP.” It was a stint that began with high hopes, stoked by an ad campaign that began with the first public revelation of the real identity of the movie actress previously known to her many fans as “Little Mary.” It soured when Pickford realized she had left Biograph for an amateurish independent. It ended in a blizzard of legal maneuvers: injunctions, suits and counter-suits, culminating in the annulment of Pickford’s contract with Laemmle.

When Universal began their “Two Marys” campaign, rumors flew that Pickford was leaving her current employer, Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players, and returning to Laemmle and his new firm. Not surprisingly, Pickford suspected that Laemmle had planted the false stories in an attempt to drive up the market for his product, specifically the Pickford/IMP back-catalogue, the thirty-three single reel films she had made in 1911. While there was no solid evidence that Laemmle was behind the rumors, it was clear that he was taking advantage of the increased demand for the Pickford product as would any astute businessman — and Laemmle was among the best, and most aggressive, in the burgeoning film industry (though at the same time he boldly predicted the impending “doom” of the feature film, a spectacular misread of the future of movies).

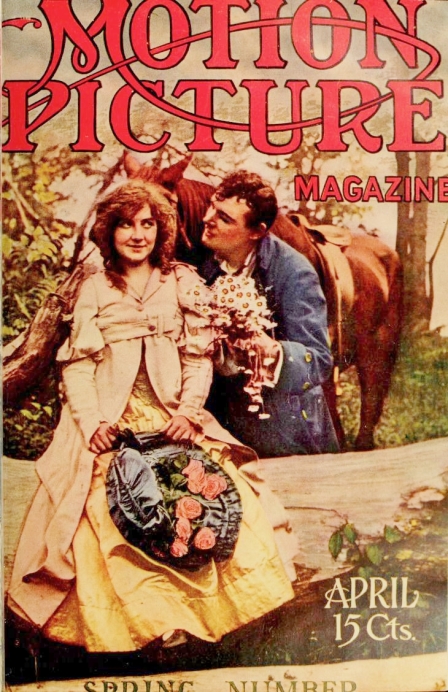

Mary Fuller with Ben Wilson, a love interest in her six part Edison serial, Who Will Marry Mary? (July-Dec 1913, dir. Walter Edwin), on the cover of Motion Picture Magazine, April 1914.

Laemmle’s acquisition of the “other Mary,” Fuller, appeared to be a genuine coup all by itself. Fuller was at the peak of her popularity and the first star of movie serials — a product that allowed filmmakers, distributors and exhibitors to find a middle ground between the two competing formats, the single reel short versus the multiple reel feature films that had come to dominate both imports and domestic product by 1914. It wasn’t exactly a new concept. Just as single reel films mimicked the ubiquitous literary short story form, the serial films were essentially throwbacks to early nineteenth century publishing practices in which novels were issued in periodic installments that served to heighten interest with each new part, and spread out the financial impact on book vendors and consumers. The Edison serials starring Mary Fuller were so successful that they inaugurated a “craze” for the serial format.

Fuller had made more than a hundred shorts for both Vitagraph and Edison between 1908 and 1912, before appearing in her first serial for Edison, the twelve part What Happened to Mary. True to the origins of the format, it was based upon a recurring fiction series in the McClure Publishing Company’s Ladies World magazine. Edison followed the phenomenal success of that initial serial with Who Will Marry Mary? (1913) in six installments, and in January of 1914 the first of twelve episodes of The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies.

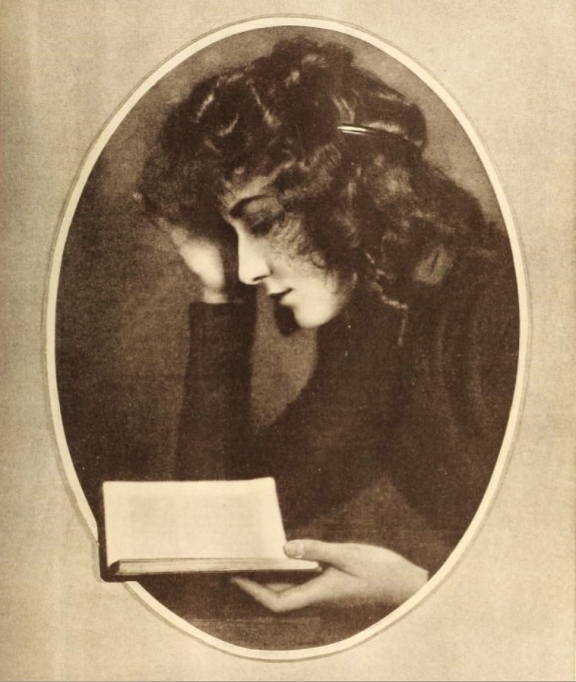

But Mary Fuller wasn’t merely a serial queen. She made dozens of one and two reel shorts for Edison between episodes of her serials, maintaining a dizzying work load that saw her before the camera for sixteen hour days, six days a week, with only Sundays for rest and recreation at restaurants, plays and concerts, on long automobile drives, or walks on the beaches of Long Island with assorted male companions — as she described in her poignant “Extracts from the Diary of Mary Fuller” in Motion Picture Magazine. However, by early 1914 there are indications that a rift was developing between Fuller and Edison.

Like the Edison/Fuller “Mary” serials, The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies was planned as a monthly series — each of the twelve episodes would be released on the last Saturday of the month. But shortly after the premiere of the first installment, Edison announced that due to exhibitor demand not one but two “Dollys” would be released each month beginning with episode three in March. This revised release schedule of course meant the acceleration of an already brutal work load for Fuller. Not only did she act, but she also wrote scenarios (though not for the serials), provided (and sometimes made) her own costumes and performed her own stunts, including an explosion that went awry in “Dolly” episode No. 7.

Shooting on “Dolly” had begun hard on the heels of the last episode of Who Will Marry Mary?, and during the production of “Dolly” Fuller made another dozen separate films for Edison. She may well have decided that a star of her magnitude could do better than merely grinding out reel after reel of product, the film equivalent of sausages. And with Universal she may have sensed a new opportunity: to create quality rather than mere quantity.

Edison must have known that Fuller was on the verge of leaving them for another producer — not only Fuller, but her frequent director Walter Edwin and co-star Charles Ogle would leave with her. Negotiations involving three of Edison’s most important employees with another producer, particularly the garrulous Laemmle, could hardly have been kept quiet for long. Edison curtailed promotion of the “Dolly” series in May, after the release of Episode No. 7, The End of the Umbrella — the episode in which Fuller was injured in a stunt. On June 20, 1914, the deal with Universal was closed, several weeks before shooting wrapped on The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies.

Edison must have known that Fuller was on the verge of leaving them for another producer — not only Fuller, but her frequent director Walter Edwin and co-star Charles Ogle would leave with her. Negotiations involving three of Edison’s most important employees with another producer, particularly the garrulous Laemmle, could hardly have been kept quiet for long. Edison curtailed promotion of the “Dolly” series in May, after the release of Episode No. 7, The End of the Umbrella — the episode in which Fuller was injured in a stunt. On June 20, 1914, the deal with Universal was closed, several weeks before shooting wrapped on The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies.

Ironically, Mary Fuller chose to sign with a man who publicly disdained the “long feature” — the same Carl Laemmle from whom Mary Pickford had fled in disgust at the lack of professionalism. But that was in 1911, and now, in 1914, that seemed nearly a lifetime ago in the rapidly evolving art and industry of moving pictures. Both Pickford and Fuller had reached a level of personal success and industry recognition that now found them on the same double-paged ad in The Moving Picture World. In reality, each came from very different worlds.

* * *

The Pickford story is well-known: Toronto. Extreme poverty. Absentee alcoholic father. Widowed mother three children. Family rises from poverty on the talents of the child Gladys Smith. By contrast, Mary Fuller’s opening act is much less remarkable, if also much less depressing.

Mary Claire Fuller was born October 5, 1888, the second child in an upper middle-class family in Washington, D. C. (Fuller’s birth date is subject to debate. The October 5, 1888 date is contradicted by a discrepancy between two separate death certificates issued for Mary Fuller, both with the same Social Security Number. The second death certificate gives a birth date of July 2, 1888. Incredibly, two separate death dates are also given. Further complicating matters, Fuller herself gave her age as 28 in the 1915 New York State Census, conducted in June, 1915, in which it asked for age on most recent birthday. Depending on which birthday she chose to answer the census question, Fuller’s correct year of birth could be 1886 or 1887.)

Fuller’s father, Miles Fuller, was a successful Washington lawyer and business-owner who also worked for the U. S. Department of Agriculture, but died young: at age 44 in 1902. He left a wealthy widow. (In 1909, Mary’s mother, Nora Swing Fuller married a prominent politician, Dr. Leander F. Cain, an Ohio native who had moved to Oklahoma, quit practicing medicine and entered politics. The couple eloped and were wed in Rockville, Maryland without the foreknowledge of Mary or her two sisters. Cain ran unsuccessfully for the second Governorship of the new state of Oklahoma on the Republican ticket in 1910. The couple were divorced in 1914.)

In her teens, Mary began to appear in local amateur productions, first attracting attention in the press as Miss Claire Fuller. In 1905, The Washington Post noted her work with The Thespians, a well-regarded amateur company of players,

“. . . one of the best and most evenly balanced amateur companies in the city. All the members are well-known. . . Miss Claire Fuller played the romantic young daughter of the major.” The Washington Post, Sunday March 12, 1905.

Like many stock company actors, Fuller saw the movies as a way to escape, if only temporarily, the grind of a traveling player. As she told Motion Picture Magazine in 1914, she had been stranded in New York City after her stock company folded during the Christmas season (apparently 1907) and having “the movies” still ringing in her ears as a possibility, decided to visit a studio, Vitagraph in Brooklyn. After a single interview Fuller was hired for a small part. She spent 1908 and most of 1909 with Vitagraph, then signed with Edison making more than eighty short films of all genres. She was among the first film actors to be profiled extensively in the early film fan-oriented magazines; her frequent appearances in these periodicals, her frequent mention in fan mail reprinted in the magazines and her high “ranking” in the strange and quite unscientific fan polls all give evidence of her tremendous popularity in an era where moviegoers were only beginning to learn the names of some of their favorite film players.

1914 would prove to be the peak year of success for Mary Fuller, and although she would maintain that level of stardom for another two years, the “other Mary,” Pickford, had already surpassed her to become the player most in-demand by audiences, exhibitors, and producers — the flap over the unprecedented re-release of her “old” films, the three year old “IMPs,” proved that. Pickford would continue to build a following, a career and a legend, while Fuller’s story, seemingly the reverse, has yet to be fully understood and told. In a future installment, hopefully not entirely inadequate, I will attempt to tell the remainder of that tale.

* * *

In 2010, Episode No. 5 of The Active Life Dolly of the Dailies, “The Chinese Fan,” was one of 75 films found in the New Zealand Film Archive and repatriated to the U.S. with the cooperation of the National Film Preservation Foundation. It was restored and premiered in Los Angeles later that year. It is the only known surviving episode of the historic “Dolly” serial. It was recently broadcast on TCM, as part of a DVD collection of films from that historic discovery.

In late March of 1914, Cecilie Petersen, a staff writer for The Motion Picture Story Magazine, visited the Edison studios in the Bronx, New York. While touring the campus and the facilities, Ms. Petersen stumbled upon a group of actors rehearsing a scene. Although the writer did not know what they were rehearsing, with the benefit of a century’s hindsight we can see that it was, amazingly, that same once-lost film, “The Chinese Fan,” Episode No. 5 of The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies . . .

The Edison studio, 1914, abuzz with activity. Motion Picture Story Magazine, June 1914.

“The music ceased. . . Suddenly there came an interruption from behind us.

‘Oh, Mr. Osborne, Mr. Osborne!’ cried an excited voice. ‘Oh, I’ve had such luck! There was a fire at the hotel; I was there, and who do you think I saved and brought here? Look! It’s Muriel Armstrong!’

“I turned in some astonishment. The voice was charged with such real excitement, that for a moment I wondered whose it could be. I might have known. It was Mary Fuller, ‘Dolly of the Dailies,’ herself, rehearsing a scene for her series. Her pretty hair was slipping down over her ears, her cheeks were ablaze with color, her eyes sparkling as she told her story to the editor. Bessie Learn, as Muriel Armstrong, reclined wearily in an office chair, scarcely noticing what was going on.

‘Hey, boys!’ shouted the editor, ‘here’s Muriel Armstrong!’

“Two or three reporters, Yale Boss among them, ran in and gazed at the girl unbelievingly. The editor turned.

‘Come, little girl,’ he urged. ‘You’ll give us your story, won’t you?’

‘But the girl shrank back, terrified. Miss Fuller went a little nearer and laid her hand on the arm of the chair. ‘Tell us all about it,’ she said gently. The girl began weakly.

‘Chinamen?’ prompted Dolly. Yes, Chinamen.’

“The girl caught at the word eagerly and continued with her story, while the reporters joyously took down the ‘big scoop.’

“It was all very realistic and very thoro [sic]. Miss Fuller takes her work very much to heart, and she has managed to instill the same point to view into the rest of the company.

“The rehearsal over, I turned regretfully toward the door. The studio has a strange fascination for all who come near it. It is a busy place, but the work is of a kind that seldom palls, no matter how hard it is.”

“A Visit to the Edison Studio, by Cecilie B. Petersen,” Motion Picture Story Magazine, June, 1914.

* * *

Primary sources:

Public Records: U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989; U. S. Social Security Death Index, 1935-Current; New York State Census, 1915; all via Ancestry.com.

Periodicals and newspapers: The Moving Picture World, Motion Picture Magazine, Motion Picture Story Magazine, Motography and Film Fun Magazine, all via The Media History Digital Library at mediahistoryproject.org); The Washington Post (for the 1909 marriage and 1914 divorce of Nora Swing Fuller and Dr. L. F. Cain; and Mary Fuller on stage in 1905) via Ancestry.com

Photos & illustrations (excluding those reproduced from the above periodicals): Still frames from The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies, Episode No. 5, “The Chinese Fan,” (Thomas A. Edison, Inc., 1914; Academy Film Archive, 2010) from TCM broadcast 11.24.2013 of The National Film Preservation Foundation DVD, Lost and Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive, Image Entertainment (2013).