Part One: THE IMP and THE MAJESTIC

Why did Mary Pickford, whose fame in 1911 was due almost exclusively to her movies, appear on the cover of The New York Dramatic Mirror, an honor normally granted to stars of the “legitimate” theater? The featured article in this particular issue was a discussion of “Personality in Acting,” a subject of debate among devotees of the stage. But “personality” or star-power was rapidly becoming the focus of film, and Mary Pickford was in 1911 already its foremost exponent.

* * *

Until the last decade, Mary Pickford’s career was not afforded the close analysis and discussion as were the careers of her contemporaries, her peers. This is astonishing given that she has no equal — no true equivalent — in cinema. The primary source of this neglect can be traced to the actress herself. Upon her retirement from acting, she refused to lease the rights to her films, including the early Biographs that she had purchased, as well as those she already owned outright through her production company. As a result, informed discussion and study of her work essentially ended with the memories of those who first appreciated her films during her active years as an actor and filmmaker.

Writers and “historians” who dealt with her work in subsequent generations generally accepted what had been an uninformed, superficially constructed and false notion that Pickford was an artist fatally infected with an artificially sweet sentimentality, and that she was an aging silent film actress who insisted on portraying young girls up to the dawn of sound. Not until the rerelease of her films in public screenings and on home video more than a decade after her death in 1979 was the public given the opportunity to revisit and reappraise the inestimable contributions of this seminal figure of cinema. I don’t believe this excuses the shoddy or even non-existent efforts by those who claim to be film scholars or historians and who write for serious academic purposes, or even those who write for popular publication and profit. It seems to me stunning that the first in-depth biographies of Pickford did not appear until the late 1990s, and that a thorough study of her films has yet to be written and published.

Mary Pickford’s movie career can be divided into roughly three phases. The first is the beginning of her career with Biograph and D. W. Griffith — a period subdivided by a stint of just over 12 months from late 1910 to early 1912 with Carl Laemmle’s Independent Moving Pictures (IMP) Company and Harry Aitken’s Majestic Film Manufacturing Company (with whom Griffith himself would sign after leaving Biograph in 1913). The second was the start of her feature film work with Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players company, the period in which she became a media star in the modern sense. The third was the period in which she began to oversee the production of her work, and then its distribution through United Artists of which she was one of the founders — a period during which she was at various times the highest paid actor on Earth and the most powerful woman in the movies.

Because most of the Griffith Biographs have escaped total destruction, virtually all of Pickford’s earliest work with that company still exists. Her United Artists releases, covering her peak years beginning in the late 1910s, have likewise survived relatively unscathed. But a significant number of her earliest feature films, the ones in which she began to define herself as a maturing artist, are gone, lost to nitrate decomposition or combustion. Also, most of the single reel films she made with the two independents, IMP and Majestic, are lost, denying us the opportunity to compare them with those she made both before and afterward at Biograph with D. W. Griffith.

The movie production stills and memorabilia that survive — many of which are contained in volumes such Christel Schmidt’s new compilation of images and essays Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies (Kentucky, 2012), and Kevin Brownlow’s earlier Mary Pickford Rediscovered: Rare Pictures of a Hollywood Legend, (Abrams, 1999) — are among the few physical records remaining of those films now lost. What follows is a pictorial sampling of some of those early films, the independent one-reel productions and the early features, in the form of the original descriptive advertisements and actual reviews in contemporary publications, along with my commentary.

* * *

The IMP.

The identity of “Little Mary” was officially revealed for the first time in the press on December 24, 1910 in The Moving Picture World. After toiling anonymously in films for nearly two years, she was now: “Miss Mary Pickford” of the Independent Moving Pictures Company (IMP). It was an arrangement that would falter almost as quickly as her impending marriage to actor Owen Moore.

The identity of “Little Mary” was officially revealed for the first time in the press on December 24, 1910 in The Moving Picture World. After toiling anonymously in films for nearly two years, she was now: “Miss Mary Pickford” of the Independent Moving Pictures Company (IMP). It was an arrangement that would falter almost as quickly as her impending marriage to actor Owen Moore.

Mary Pickford was both a balm and a trophy to Carl Laemmle. He and his IMP Company had lost their biggest star, Florence Lawrence, to the Lubin Company in late 1910 after he had signed the former “Biograph Girl” a year earlier and made her the focal point of the first ad campaign for a film personality, creating in essence the first “movie star”.  Pickford, having inherited the “Biograph Girl” mantle by default, already had a sobriquet,”Little Mary,” and she acquired an intense and loyal fan base of her own. At Biograph she received $100 a week but without name recognition. Laemmle offered her $175 per week, reams of press publicity and, almost as important, places for brother Jack and sister Lottie on the IMP payroll. He had already employed her lover, Owen Moore, after Moore had been fired by Griffith. Pickford and Moore would marry in secret on January 7, 1911, two days before the release of her first IMP production, co-starring Moore, the aptly titled, Their First Misunderstanding. It would not be their last.

Pickford, having inherited the “Biograph Girl” mantle by default, already had a sobriquet,”Little Mary,” and she acquired an intense and loyal fan base of her own. At Biograph she received $100 a week but without name recognition. Laemmle offered her $175 per week, reams of press publicity and, almost as important, places for brother Jack and sister Lottie on the IMP payroll. He had already employed her lover, Owen Moore, after Moore had been fired by Griffith. Pickford and Moore would marry in secret on January 7, 1911, two days before the release of her first IMP production, co-starring Moore, the aptly titled, Their First Misunderstanding. It would not be their last.

Their First Misunderstanding (IMP, 1911, directed by Thomas Ince). Long thought to be among the lost Pickford IMPs, a nitrate copy of Their First Misunderstanding was found in 2006 among a cache of films stored in a New Hampshire barn. Restored in 2013, it was “premiered” October 11, 2013 at Keane State College, in a program hosted by Pickford scholar and author Christel Schmidt. Originally released January 9, 1911, this one-reel, 997 ft. comedy-drama was Mary Pickford’s debut with the IMP company and her first name-credited film role. Co-starring her husband of two days, the film was given a perfunctory review and treated as an average, passable release by the editorial staff of The Moving Picture World.

Their First Misunderstanding (IMP, 1911, directed by Thomas Ince). Long thought to be among the lost Pickford IMPs, a nitrate copy of Their First Misunderstanding was found in 2006 among a cache of films stored in a New Hampshire barn. Restored in 2013, it was “premiered” October 11, 2013 at Keane State College, in a program hosted by Pickford scholar and author Christel Schmidt. Originally released January 9, 1911, this one-reel, 997 ft. comedy-drama was Mary Pickford’s debut with the IMP company and her first name-credited film role. Co-starring her husband of two days, the film was given a perfunctory review and treated as an average, passable release by the editorial staff of The Moving Picture World.

However, a reviewer from the MPW‘s competitor, The Moving Picture News, raved about the inaugural Pickford/IMP release:

“I went on purpose to see this film and afterwards hugged myself that I did. There wasn’t a seat empty that I could see in the Fourteenth Street Theater . . . The reel was a solid, undoubtful success. Welcome, ‘Miss Mary,’ you surely are a ‘darlint’ and got a welcome that you deserved. Didn’t that audience laugh! The staging, acting, photography, everything was all right. The humor . . . filled the theater with laughter. Miss Pickford was a real woman and carried the great audience along with her.” Review by “Walton,” The Moving Picture News, January 21, 1911.

Theater owners in cities as varied as Boston and Omaha found business brisk for both Mary Pickford and Their First Misunderstanding.

The news from Boston, however, ends with a vaguely ominous note, “Licensed exhibitors are viewing the strengthening of the independent manufacturers’ stock companies with more or less seriousness — and questioning.” To Laemmle and IMP, this was understood as the not-so-vague threat of potential violence against the independent film companies, and keeping his crews and equipment out of harm’s way — as far away as was practical — might be the best course of action for a while. Coincidence or not, by the end of January Laemmle would send his production crew and stock company out of the country at least temporarily: to Cuba.

This Omaha theater-front, littered with signs for IMP movies, including several for Their First Misunderstanding, appeared in the Feb 4 issue of The Moving Picture World. At far right the poster shouting, “EXTRA,” appears to have misspelled her name as Mary Pickerd!

The second Pickford IMP, The Dream, again co-stars Owen Moore, and was released two weeks later on January 23, 1911, also directed by Thomas Ince. What both films had in common was the theme of a drunken and/or neglectful husband who learns the errors of his ways after mistreating his wife. Pickford, who had written film scenarios for Biograph, did not write either IMP scenario, although she would shortly be able to write similar plots from first-hand experience.

Two reviews of The Dream appeared in The Moving Picture World, January 21 and 28, 1911 (the first is actually just a story synopsis, the second a “Commentary on the Films”):

The Dream was believed lost until a copy was found and restored in the late 1990s and released to home video as a DVD “extra” on the Milestone Films 1999 restoration of Pickford’s 1918 feature, Amarilly of Clothesline Alley. One can only speculate what Pickford felt as she made the transition from Biograph to the IMP Company, and we should not draw conclusions about the relative merits of the two producers based solely upon this half-reel, five-minute comedy, but Biograph had been making superior films in this genre three years earlier.

Those three years — 1908 to 1911 — represent a period of tremendous development for many filmmakers, including D. W. Griffith. Earlier examples of similar short comedies from Biograph in 1908-09 are Lucky Jim and The Gibson Goddess, both with Marion Leonard, and The Little Darling with Pickford. By 1911, Griffith had handed over such films to Biograph’s “comedy unit,” headed by Mack Sennett who was making films far more imaginative than The Dream. Nonetheless, Pickford lights up the screen with an adult variation on the wild-girl, “harum-scarum” character that she had played so effectively at Biograph.

As the film begins, Pickford plays what at first appears to be a stock character of the neglected wife whose husband comes home loaded and angry, smashes some dishes, throws a few chairs, then passes out on the couch. But then he dreams.

He awakes to find his little wife a wild-woman of the boulevard, a curvaceous hellcat dressed to kill who swills brandy, lights up a smoke, tosses the match into his face and drop-kicks the china, all before going out to party ’til dawn just as he had.

The husband follows her, sees her cavorting with another man, goes home and shoots himself. He awakens. He is not dead. His wife is not a wild woman. It was all a terrible dream — a nightmare. He is suitably chastened and spends the rest of the evening and, if he is smart the rest of his days, pleasing her.

Most of the charm of this film comes from the contrast Pickford gives us between the “real” and the “really wild” wife. The Dream might be an ideal, quick introduction to Mary Pickford for someone who has the misconception of her as a saccharine sweetheart. It appears that at least one reviewer from The Moving Picture World felt just a bit disoriented by this vision of a thoroughly adult Pickford:

“We felt the same misgivings a father must feel when he observes his daughter as she stands on the threshold of womanhood . . . It has never occurred to us that she might grow up and become a woman some day, but judging from her delineation of the matron, we have every reason to expect that her past experiences in playing ingenue roles will be merely an epoch in her advancement and her final success as a leading woman.” The Moving Picture World, January 28, 1911.

The reviewer, obviously familiar with Pickford’s Biograph work, refers to her past experiences “playing ingenue roles,” in other words young women, but not children, as she had only on rare occasion played a child (and in fact often played married women with children of their own). Pickford could have found the reviewer’s words instructive, even comforting, a decade later when she struggled with the contradictions and constrictions that her image as “America’s Sweetheart” had placed on her as an artist. In the meantime, she committed the perfectly adolescent act of marrying her sweetheart in secret. She would have to take her mother, brother and sister along for the honeymoon, agonizing over how to break the news to them, all the while trying to establish her film career post-Griffith and Biograph, standing on her own as “Mary Pickford.”

Above, a rare full-figure advertisement for Mary Pickford in Her Darkest Hour, a single-reel drama. The last IMP film Pickford completed in New York prior to the company’s Cuban excursion, Her Darkest Hour, now a lost film, was released with The Convert, in mid-February 1911. Above right, short reviews from the MPW for Her Darkest Hour and two other Pickford IMPs which do exist, the split-reel 500 ft. comedies The Mirror and When the Cat’s Away, both from the first week of February.

CUBA, 1911.

This photo originally appeared in The Moving Picture World, February 11, 1911, with the caption, “The IMP Stock Company . . . are well-known to thousands of movie-goers all over the world for their excellent work.” They also do not look like the merriest band of thespians and technicians.

Pickford, newly wed to Owen Moore, does not appear the happy bride. She is second row, center, surrounded by Moore (to her right, hands crossed), actor King Baggot (a major star at the time, to her left), and in the same row at far left to the viewer is the director, soon-to-be producer and major Hollywood player of the late teens and early 20s, Thomas Ince. In the back row are David Miles (the tall man second from left, Pickford’s co-lead in her first important Biograph role from 1909, The Violin-Maker of Cremona), and Antonio “Tony” Gaudio (second from right with vest and handlebar moustache), a recent immigrant from Italy who would become one of the great cinematographers in film history over the next fifty years. Seated in the first row are the younger, sullen Pickfords, Jack (center) and Lottie (right).

Shortly before this photo appeared, Carl Laemmle shipped his IMP crew to Cuba, ostensibly to give them a better climate for outdoor filming in mid-winter and an interesting exotic background for tropical romances and tales of adventure in the Caribbean. But as Pickford explained in her autobiography, the move was made to avoid violence. Shotguns and sledgehammers had pummeled both equipment and crews of other “independents.”  The IMP Company had already been threatened (and according to Pickford, stoned) by hired goons from the Motion Picture Patents Company, the “MPPC,” a trust company that included Biograph, from whom Laemmle had signed Pickford, her two siblings Jack and Lottie, and actor David Miles.

The IMP Company had already been threatened (and according to Pickford, stoned) by hired goons from the Motion Picture Patents Company, the “MPPC,” a trust company that included Biograph, from whom Laemmle had signed Pickford, her two siblings Jack and Lottie, and actor David Miles.

Mary Pickford waited until the Cuba trip to tell her family that she had secretly married Owen Moore several weeks earlier. Mother Charlotte was not pleased (she hated Moore even before this development). Jack and Lottie cried and refused to speak to their sister. Moore got drunk and stayed that way for much of the trip. In fact, his behavior would soon precipitate not only an early end of the Cuban trip for Pickford and him, but their employment with IMP as well.

Above, IMP announces its trip to the tropics, urging movie exhibitors to “Watch for the Cuban Imps, the Florida Imps, the Mexican Imps,” and in the meantime, to “get after these Imp releases,” that were made prior to the Cuban trip, including Maid or Man, a surviving split-reel comedy “of the ‘Little Mary’ series,” warning that “you must not miss a single blessed one of these! Get busy!” From The Moving Picture World, Jan. 28, 1911. For the record, there were no “Florida” or “Mexican” IMPs — at least none with Mary Pickford in them.

Below, the first of the “Cuban” IMP productions to be released was Pictureland on February 20 — Pickford apparently appeared only in the film’s introductory scene which showed the arrival in Cuba of the IMP company. Not surprisingly, the first Cuban IMPs had hispanic themes and settings, and were promoted as such. While the MPW couldn’t decide how to classify Pictureland with its emphasis on locale (drama? comedy? travelogue?), the first Pickford IMP shot in Cuba, Artful Kate, a single reel drama released just days later, seems to have impressed the reviewers of the MPW more, not only with its tropical scenery and photography, but also with its story and the performances. Pictureland is a lost film, while Artful Kate is extant in multiple archives. [Note: As of July 2015, Pictureland appears to have been found, see this thread at the Nitrateville website.]

Above, The Message in the Bottle, a lost film, seems to have been an early swashbuckler, with Cuba and the Caribbean an ideal backdrop for shipwrecked sailors, romance, and “dusky” maidens who inhabit the tropical isles. (In my head, I keep hearing theme music for this lost film — could it be Sting?)

Moore’s drinking and violent temper would cause the Pickford/IMP Cuban experiment to go completely awry when after completing several films, Moore got into a violent altercation with his assistant director and narrowly avoided arrest by Cuban police when Mother Charlotte was able to get him onto a boat leaving immediately for the mainland. But she had to talk Mary into going with him.

The remainder of the IMP Company returned home from its Cuban expedition in the spring, judging by their ad copy (touting each release “Made in Cuba”), sometime in late March or early April, 1911. (The last IMP described as being shot in Cuba was, appropriately, A Good Cigar, a non-Pickford IMP, released April 10, 1911.)

Below are two more lost IMP films, shot in the U. S., The Call of the Song (released August 3) and The Toss of a Coin (August 31), previewed in articles in The Moving Picture World. Judging by their descriptions here, both films were light dramas of the tribulations of love lost, then regained.

Above, a scene from The Toss of a Coin, from The Moving Picture News, August 12, 1911.

Above, a scene from The Toss of a Coin, from The Moving Picture News, August 12, 1911.

A late Pickford IMP that does exist and was reissued by Blackhawk Films (and later in a DVD version on Nickelodia 2, by “Unknown Video”), is As a Boy Dreams, released August 24, 1911. Judging by the exteriors (the Hudson River Palisades in the boat scene), the IMP crew and Mary Pickford were back in the States when this film was shot.

The Moving Picture World was being kind in stating the film’s “interest is small . . . the picture is acceptable.” It is an embarrassing mess, one that if we weren’t otherwise aware we would surely think was from 1904, at the dawn of narrative film. Pickford is clearly embarrassed to be part of it, and in nearly every static shot of the film, she is downcast, or biting her knuckles, or simply turning her face from the camera. The plot is not worth recounting. Suffice it to say that Pickford suffers the ignominy of marriage to a twelve-year-old boy — if only in his dream. (You can click on the above excerpts from the MPW reviews and click for full-size images from the film, below.)

Below, ‘Tween Two Loves, another late IMP for Pickford, a one-reel drama released September 29, 1911, was given special coverage by the MPW in their “Reviews of Notable Films.” The MPW editorial board was given a special preview of the film, and were pleasantly surprised by the quality. Given what had just come before it, ‘Tween Two Loves must have seemed like a milestone of cinematic art. Or maybe not. We do know that it exists in two archives, the Library of Congress and the George Eastman House.

The reviewer had been invited by the IMP Company to a preview of two hours worth of upcoming IMP releases. Given that none were more than one reel (10-15 minutes each), there may have been as many as eight titles screened. Noting that it was rare to find, as he did here, an entire batch of films each of quality, the writer chose to focus on one that particularly impressed him. Not to be mistaken for an early Miley Cyrus or Hilary Duff vehicle, ‘Tween Two Loves sounds like a rehash of an earlier Griffith Biograph also featuring Mary Pickford, As It Is in Life, from 1910, which itself was probably a variation on something that came before. But explaining that a simple recitation of the plot (which is often all that appeared in early film reviews) does not adequately characterize the film, the reviewer goes on to praise it effusively:

The reviewer had been invited by the IMP Company to a preview of two hours worth of upcoming IMP releases. Given that none were more than one reel (10-15 minutes each), there may have been as many as eight titles screened. Noting that it was rare to find, as he did here, an entire batch of films each of quality, the writer chose to focus on one that particularly impressed him. Not to be mistaken for an early Miley Cyrus or Hilary Duff vehicle, ‘Tween Two Loves sounds like a rehash of an earlier Griffith Biograph also featuring Mary Pickford, As It Is in Life, from 1910, which itself was probably a variation on something that came before. But explaining that a simple recitation of the plot (which is often all that appeared in early film reviews) does not adequately characterize the film, the reviewer goes on to praise it effusively:

“Thus baldly put, the story does not reveal much of interest, but the producer and the performers have deftly clothed the skeleton with the habiliments of life until every scene throbs with the realities of human existence. . . As a the whole, the production is of the highest class, and marks a distinct advancement in the character of the work of the IMP Company.” The Moving Picture World, “Reviews of Notable Films,” Sept. 16, 1911.

The career of Mary Pickford at the IMP Company effectively ended before summer was out — and IMP had stopped mentioning “Little Mary” in their trade paper ads weeks earlier. Yet, October saw the release of four films she had previously completed, The Rose’s Story, The Sentinel Asleep, The Better Way and His Dress Shirt, none of which exists. One final Pickford IMP, A Timely Response was reviewed in the MPW the following March, 1912, described as a rerelease under a new title, The Wife’s Desertion. It received a favorable review, and Mary Pickford was named-in-full (as opposed to the “Little Mary” she still typically received, almost eighteen months after her full identity was revealed to the press), but by that point, Pickford had long since moved on.

The career of Mary Pickford at the IMP Company effectively ended before summer was out — and IMP had stopped mentioning “Little Mary” in their trade paper ads weeks earlier. Yet, October saw the release of four films she had previously completed, The Rose’s Story, The Sentinel Asleep, The Better Way and His Dress Shirt, none of which exists. One final Pickford IMP, A Timely Response was reviewed in the MPW the following March, 1912, described as a rerelease under a new title, The Wife’s Desertion. It received a favorable review, and Mary Pickford was named-in-full (as opposed to the “Little Mary” she still typically received, almost eighteen months after her full identity was revealed to the press), but by that point, Pickford had long since moved on.

His Dress Shirt, directed by Thomas Ince, was the last Pickford IMP released while she was still under contract to the company. She is paired opposite William Robert Daly in this split reel 750ft sitcom previewed here October 8, 1911 in The Moving Picture World, and released on October 30. Once her contract with IMP was annulled by the courts, she began working at Majestic in November.

His Dress Shirt, directed by Thomas Ince, was the last Pickford IMP released while she was still under contract to the company. She is paired opposite William Robert Daly in this split reel 750ft sitcom previewed here October 8, 1911 in The Moving Picture World, and released on October 30. Once her contract with IMP was annulled by the courts, she began working at Majestic in November.

After leaving Cuba prematurely along with Moore, Pickford continued with IMP, and claimed later in her autobiography that she left when her contract was up. But legal action by Laemmle would indicate that he did not concur.

In reality, Pickford had left IMP ostensibly in violation of her contract with Carl Laemmle’s company. Laemmle sought an injunction to prevent her from working elsewhere, forcing Pickford to testify in court as to the embarrassment and humiliation she had endured as an IMP. In her defense, she cited intolerable and unprofessional working conditions for an acclaimed actress — it was “an affront to her art,” she told the judge. She had been nearly killed by an out of control motor boat operator while filming in the Hudson River, had contracted some tropical illness in Cuba that caused her to lose weight, and had to suffer working opposite non-professional actors, such as the lab assistant who was a relative of a company executive. The court threw out the injunction request and ruled the contract unenforceable on the basis that Pickford was still a minor (eighteen) when she had signed the agreement with Laemmle.

[I find this event very curious. An astute businessman by all accounts, Carl Laemmle had to have been aware that Pickford was underage and therefore unable to enter into a binding legal agreement unless she had co-signed with a parent or other adult guardian or legal representative. She was a minor and single at the time — she and Owen Moore were not married until after they signed with IMP. Mother Charlotte was Pickford’s chief negotiator in all of her financial dealings and was also as shrewd a businesswoman as her daughter would become. Maybe the Pickford IMP contract was drafted in error. Maybe “Uncle Carl” wasn’t as astute a businessman. After all, this is the same Carl Laemmle who as head of Universal seven years later unleashed upon Hollywood the profligate director Erich Von Stroheim. At least his mistakes, if they were such, were made over geniuses of their kind. It doesn’t seem as if anyone has bothered to research beyond the press accounts and check the legal records, and a more complete answer, if one exists, is likely to be found there.]

The Majestic.

Above: The cover of The Moving Picture News featured the three principals of the new Majestic Motion Picture Company, with Pickford the “rose between two thorns” of husband/lead actor/director Owen Moore and general manager Tom Cochrane. The MP News article inside this September 23, 1911 issue scooped rival The Moving Picture World, Below, by nearly a month.

Pickford had a new contract, with Harry Aitken’s new Majestic Motion Picture Company, a new salary of $225 per week, and Jack and Lottie on the payroll along with Owen, whom she convinced Aitken to take on as an actor and director. Their marriage, already shaky, would not survive it. Her new situation with Aitken and Majestic and Owen would last for only five films.

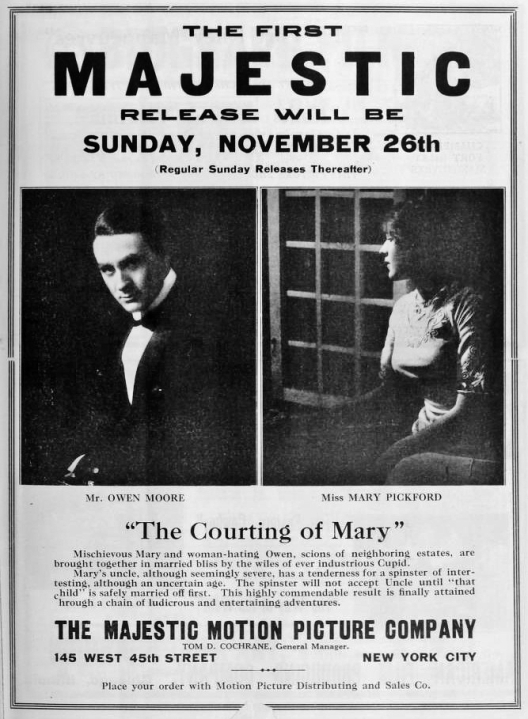

The Courting of Mary (and Owen).

Harry Aitken’s blunt, provocative promotion of Mary Pickford’s first Majestic release was about as far from Carl Laemmle’s comical, needling promotions of “Little Mary” as one could get. The trade paper ads featured the movies’ most famous couple in a film with a title that seemed to coyly describe the couple’s real-life romantic history, The Courting of Mary. They were paired as “Mischievous Mary” and “woman-hating Owen,” accompanied by chiaroscuro photo portraits of Moore, simultaneously pensive and menacing, and of an apprehensive (and bosomy) Pickford.

Harry Aitken and his brother, Roy, were film distributors who operated a large network of film exchanges — rental outlets for theater owners who would subscribe under contract for the films distributed by The Majestic Film Exchange Company. Breaking away from association with the MPPC trust companies, who refused business to any exchange dealing with “independent” films, the Aitkens gradually acquired movie production companies under the umbrella of The Majestic Film Manufacturing Company. Apparently having followed the Pickford/IMP situation closely, Harry Aitken approached Pickford probably not long after her return from Cuba in mid-summer of 1911 with an offer to work with his newly created production unit, The Majestic Motion Picture Company. Negotiations concluded with Aitken agreeing to employ both Pickford and Moore, with Moore as both actor and director. They would each receive $225 per week and, of course, Jack and Lottie were picked up as well.

Harry Aitken and his brother, Roy, were film distributors who operated a large network of film exchanges — rental outlets for theater owners who would subscribe under contract for the films distributed by The Majestic Film Exchange Company. Breaking away from association with the MPPC trust companies, who refused business to any exchange dealing with “independent” films, the Aitkens gradually acquired movie production companies under the umbrella of The Majestic Film Manufacturing Company. Apparently having followed the Pickford/IMP situation closely, Harry Aitken approached Pickford probably not long after her return from Cuba in mid-summer of 1911 with an offer to work with his newly created production unit, The Majestic Motion Picture Company. Negotiations concluded with Aitken agreeing to employ both Pickford and Moore, with Moore as both actor and director. They would each receive $225 per week and, of course, Jack and Lottie were picked up as well.

The new production company began filming the first Pickford/Majestic production, The Courting of Mary, the first week of September, 1911. The presence of actor/director and former Biograph colleague, James Kirkwood, a friend of both Moores, may have helped alleviate the tension of having to play opposite her partner in a rapidly deteriorating marriage (Kirkwood would become a frequent director of Pickford’s feature films a couple of years later).

The Courting of Mary was not released until the end of November 1911 — the first new release by Majestic. The announcement “Owen Moore and ‘Little Mary’ with Majestic” in the Oct. 21 issue of the MPW gave the likeliest explanation. It was noted that Majestic “has finally secured the services” of Pickford, and that “another company had claimed” them and sought to prevent them from working elsewhere, a vague acknowledgment of the injunction sought by Laemmle. The film was likely in an incomplete state at the time of the decision, so even if shooting had commenced or finished, a final edit and print would most likely have been delayed until the court ruled on the matter in favor of Pickford and Majestic in the latter part of October. The film premiered November 26 to good, not great, reviews. The Courting of Mary is a lost film, as are all but one of the five Pickford Majestics.

The Courting of Mary seems to have had little in the way of a plot, more episodic than linear, its primary attraction being the presence of the two stars, feuding on film (as they had done unknown to the public from the very start of their marriage). The New York Dramatic Mirror noted the film’s “aimless tangle of disconnected incidents,” but found redemption in the appeal of the stars themselves:

“[The Courting of Mary] marks the welcome return of Mary Pickford and Owen Moore to the pictures. The personality of these two film favorites is sufficient alone to make this subject notable. No actress of her time has gained more friends than “Little Mary,” as she is affectionately called, and no leading man has wider popularity than Owen Moore. Both do pleasing work in this film, as they always do, although, to tell the truth, the story might have been better adapted to showing them at their best.” The New York Dramatic Mirror, Nov. 29, 1911.

Pickford had insisted upon Moore being hired as a condition of her employment with Majestic, and although Pickford did not divulge this to him, he most likely became aware of it while working at Majestic, where the professional and marital tension between them would soon boil over on the film set when Moore, by now dwarfed by his wife’s fame, began directing her in their next film, Love Heeds Not Showers, a romantic comedy.

Mary Pickford and Owen Moore in publicity for the release of Love Heeds Not Showers. The Moving Picture News, October 21, 1911. The film would not be released until early December. It is a “missing” Pickford film.

Mary Pickford and Owen Moore in publicity for the release of Love Heeds Not Showers. The Moving Picture News, October 21, 1911. The film would not be released until early December. It is a “missing” Pickford film.

Released just one week after The Courting of Mary, the single reel Love Heeds Not Showers did not impress reviewers:

“The reviewer would like to give the argument of this picture, or at least tell what it is all about, but although he watched it with the closest attention, he could not make it out. It has some pretty pictures. There is one instant when “Little Mary” stood close to the camera and we saw a very good portrait of this very popular player. But “Little Mary” can’t make a picture go with so poor a scenario as this behind it.” The Moving Picture World, “Comments on Films,” Dec. 3, 1911.

“There is no definite story to this picture that one would be able to find. However, the production is well put on, and presents Miss Pickford in the heights of exuberance and youthful spirits, and the other actors conduct themselves with a naturalness and levity that is altogether pleasing. If the story had dramatic form no doubt the picture would be a thoroughly artistic and interesting one.” The New York Dramatic Mirror, Dec. 6, 1911.

After a slow start, Majestic and Pickford released their third film in as many weeks, this one timed for the holiday season and aimed for a more general audience, one that included children. Little Red Riding Hood was one of the few child characters Pickford would play, either in her early short films, or in features until the late 1910s.

Little Red Riding Hood, directed by James Kirkwood,is the only Pickford Majestic to survive, albeit in severely damaged form due to nitrate decomposition, having been restored by the Library of Congress, and currently in their archives. The remaining two Pickford Majestics are A Caddy’s Dream, a split reel comedy in which Owen Moore plays a golf enthusiast who falls asleep and dreams of finding his lost ball, a search in which Pickford lends a hand. The last is Honor Thy Father, unreleased until February 9, 1912, more than a month after Pickford walked away from Majestic and Owen Moore, a single reel story of the challenges facing a young girl as she struggles without a mother and with an alcoholic father. In a way it echoed her own current struggles with a marriage damaged beyond repair by an alcoholic husband and her own inability to establish boundaries between her marriage and her family.

During the shooting of either Love Heeds Not Showers, or A Caddy’s Dream, the two Majestics that Owen Moore directed, he berated her in front of the entire crew for questioning some aspect of his direction. Up to this point, only one man could have done so without serious objection from Mary Pickford. Owen Moore was not D. W. Griffith. Mary Pickford left Majestic and Moore after the holidays. In her biography of Pickford, Eileen Whitfield notes, “The couple’s ghastly private life made work at Majestic so intolerable that they bolted after only five films. How this was accomplished remains a mystery; pertinent records and films are lost, and to Pickford the memories were unspeakable.”

She returned, the prodigal child, to D. W. Griffith and Biograph. Company records show that she completed a new film for them in January, 1912, The Mender of Nets, released February 15, just six days after Honor Thy Father for Majestic. (The Pickford Biographs of 1912 are worthy of discussion on their own, and I’ll do so at another time, though one, Friends, has already been studied in a previous post.)

Mary Pickford’s second Biograph period lasted less than twelve months, from January to November, 1912. During that period she made several of the best films of her entire career, including The Mender of Nets, Friends, Female of the Species and The New York Hat. And while it is difficult to make one-to-one comparisons between short films and feature-length films, these 1912 Pickford/Griffith Biographs rank among the most important in the development of cinema. Yet Mary Pickford was driven to try the stage again. Whether it was the reawakening of a dormant desire to become a great and celebrated figure of the theater, or whether she simply had to prove to herself that she could still do it after four years in film — a lifetime to one who is twenty — we can only speculate. But in late 1912 when David Belasco offered her a leading role in his latest stage extravaganza, A Good Little Devil, she took it without hesitation.

* * *

Of the forty films Mary Pickford made with The Independent Motion Picture Company and The Majestic Motion Picture Company, only fifteen exist in whole or in part, the remainder are gone. By contrast, every one of the 108 Biograph films in which she participated are still in existence in some viewable format. The next phase of her career, what I consider the “middle phase,” or her entrance into long-format, multiple reel “feature” films, unlike the Biographs, has major holes virtually impossible to fill. Those films will be the subject of “Missing Mary Pickford: Part Two.”

* * *

Suggested Further Reading:

Eileen Whitfield, Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood, Kentucky Press, 2007 (Paperback);

Christel Schmidt, Editor, Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies, Kentucky Press, 2012;

Kevin Brownlow, Mary Pickford Rediscovered: Rare Pictures of a Hollywood Legend, Abrams, 1999;

Mary Pickford, Sunshine and Shadow, Doubleday, 1954;

Richard Schickel, D. W. Griffith, An American Life, Limelight Editions, 1996 (Paperback).

Sources:

All of the above, plus . . .

The Internet Archive (internetarchive.org) at The Media History Digital Library (mediahistoryproject.org) for The Moving Picture World.

Archives of The New York Dramatic Mirror at fultonhistory.com, for The New York Dramatic Mirror.

Mr. Zonarich, you’ve outdone yourself with this magnificently researched profile of Mary’s work during her time with IMP and Majestic. I thought I had researched this phase of her life well when I worked on the extremely popular 2012 Mary Pickford / Owen Moore romance novel, SWEET MEMORIES, but you’ve managed to brush back the sands of time more thoroughly than even I could. Bravo for a superb piece of research and writing! -David W. Menefee, author of WALLY: THE TRUE WALLACE REID STORY, THE RISE AND FALL OF LOU-TELLEGEN, RICHARD BARTHELMESS: A LIFE IN PICTURES, and GEORGE O’BRIEN: A MAN’S MAN IN HOLLYWOOD.

Thank you for your kind words. I planned on doing this plus the missing feature films all in one article, but it was getting a bit unwieldy. Have to break it in two (she did something like 15 feature films in two years after she returned to film from “A Good Little Devil” on stage — couldn’t cover it all in one shot).

Gene, I will echo the previous comment and congratulate you on such a thorough and well-researched piece on Mary Pickford’s early years. As you say, Pickford has been glossed over by film historians for too long. This must be remedied. I can’t wait to read the next installment!

Thank you very much. Working on “Part 2” — and the “remedy” — as we speak . . .

I just wanted to say I thought I was reading an excerpt from a research book on Mary Pickford’s early works except I realized no such thing really exists and everything was researched and created by you. I found the whole article really fascinating and I really want to read more of your work on Pickford. I wish her Majestic pictures existed and I’ve been curious to view her IMP film “Artful Kate”.

Thank you. The information on which films are lost and which ones still exist came from the new book by Christel Schmidt, which I highly recommend (as well as all those listed in the “bibliography”). Schmidt has done the most thorough job of researching what exists, where it is located and in what condition, i.e., whether it is available for viewing, and is likely the most knowledgable living person on that front. Some of the information such as salaries came from the Whitfield book, and the background on Harry Aitken’s Majestic company came from Richard Schickel’s biography of Griffith. The remainder is original research, though the sources, as cited, are available to anyone. Glad you enjoyed it. Part Two is in progress, so to speak.

Thank you so much for this incredibly insightful and informative article! This is extremely well-researched and beautifully written. I love this period in Mary’s early career, and it is always exciting to discover new information about such a multi-faceted and talented woman. Looking forward to the next installment!

Thank you for the compliments. There is so much about the development of early film and, in particular the development of film acting, that can be learned by studying Mary Pickford. Unfortunately, the films that are “missing” can’t do that for us directly, so I found this to be an intriguing subject, and thought I could find at least a few traces of their existence in the media of their period. What I offer here is just a sketch or an outline, based upon a few primary sources. I actually found more than I expected, making a “Part 2” necessary. Thank you again, your kind words are much appreciated.