There was a time, far distant, when professional entertainers were not worshipped as cultural icons, and popular culture in general was considered “low” — having more of the gutter than glitter. Those who did manage to claw their way to a level of success and public approval often disguised their true origins (sometimes aided by that late 19th century creation, the professional publicist) with elaborate tales of aristocratic birth and formative years spent in the halls of preeminent institutions of higher learning before entering that devil’s den, the theatrical stage. When moving pictures became part of the entertainment available in theaters, it assumed a position at the bottom of the bill — beneath or between cheap vaudeville and tawdry burlesque.

Among the first North American motion picture players to become stars were two named Florence — Florence Lawrence and Florence Turner. Lawrence and Turner were part of the first wave of film actors — picture pioneers. Although they were among the vast majority of early film actors who came from the stage (and who typically moved back and forth between the two art forms), there was a general reluctance of stage actors to commit or even admit to film work. Anonymity and the extra cash served them well for the time being. But there quickly came a time when competition between producers erupted into war as the Edison/Biograph motion picture patents cartel attempted to shut out any “independent” competition. It forced the independent producers to look for whatever advantage they could find. And it was to the direct benefit of the moving picture players — picture “posers” who became “stars.”

Among the first North American motion picture players to become stars were two named Florence — Florence Lawrence and Florence Turner. Lawrence and Turner were part of the first wave of film actors — picture pioneers. Although they were among the vast majority of early film actors who came from the stage (and who typically moved back and forth between the two art forms), there was a general reluctance of stage actors to commit or even admit to film work. Anonymity and the extra cash served them well for the time being. But there quickly came a time when competition between producers erupted into war as the Edison/Biograph motion picture patents cartel attempted to shut out any “independent” competition. It forced the independent producers to look for whatever advantage they could find. And it was to the direct benefit of the moving picture players — picture “posers” who became “stars.”

One approach was for the independent producers to steal those familiar faces — faces without names, as yet — from the producers of the cartel. Although some cartel members, such as Vitagraph and Kalem, had released pictures and the names of their “stock companies” of film actors, Edison and Biograph had not. Biograph in particular would pay a heavy price for their continual reluctance to do so. Florence Lawrence, Marion Leonard and Mary Pickford — the top three female leads at Biograph — all left the company within a period of less than eighteen months from July of 1909 to December 1910 finding star treatment and substantial salaries elsewhere. Florence Lawrence became the first publicized star of the independents with the Independent Motion Picture Company. Florence Turner, with Vitagraph, was among the most prominent (and arguably the first) star recognized and publicized among the cartel members.

One approach was for the independent producers to steal those familiar faces — faces without names, as yet — from the producers of the cartel. Although some cartel members, such as Vitagraph and Kalem, had released pictures and the names of their “stock companies” of film actors, Edison and Biograph had not. Biograph in particular would pay a heavy price for their continual reluctance to do so. Florence Lawrence, Marion Leonard and Mary Pickford — the top three female leads at Biograph — all left the company within a period of less than eighteen months from July of 1909 to December 1910 finding star treatment and substantial salaries elsewhere. Florence Lawrence became the first publicized star of the independents with the Independent Motion Picture Company. Florence Turner, with Vitagraph, was among the most prominent (and arguably the first) star recognized and publicized among the cartel members.

A third Florence, Florence La Badie, was part of a second wave of moving picture players. La Badie was not an experienced stage actor. In fact, she had in all likelihood spent more time posing as an artist’s model than she had on stage. She wasn’t promoted as an actress as much as she was a great beauty, a feminine ideal. As such, a back story had to be created out of whole cloth rather than stage curtain: she was descended from French aristocracy, her mother a Parisian, her father an important French-Canadian official with connections to the White House, and on and on. The great irony of Florence La Badie is that these fictions and her subsequent fame concealed her true origins and clouded her death in unnecessary mystery.

* * *

On April 27, 1888, Marie C. Russ of New York City, about age 23, gave birth to a child, Florence Russ. Marie Russ, gave Florence up to adoption when she was 3 1/2. The adoptive parents were Joseph E. La Badie, about 30, a broker (financial or real estate), and his wife Amanda, in her late 20s, both of New York.

On April 27, 1888, Marie C. Russ of New York City, about age 23, gave birth to a child, Florence Russ. Marie Russ, gave Florence up to adoption when she was 3 1/2. The adoptive parents were Joseph E. La Badie, about 30, a broker (financial or real estate), and his wife Amanda, in her late 20s, both of New York.

Joseph E. La Badie had married Amanda Victor in Manhattan in 1880. Amanda, born in Germany (which explains Florence’s often-doubted fluency in German), had emigrated to the U. S. as a child in 1870. Joseph, born in Canada, United Kingdom, became a naturalized U. S. citizen on October 26, 1883. On November 4, 1891, the couple adopted the Russ child, who became Florence La Badie.

By contrast, at some point between 1891 and 1900, Marie C. Russ became a patient at the Home for the Incurables in the Bronx, as reported in the 1900 U. S. Census. She stated she was a widow, age 34, born in Ireland in 1865, who had emigrated to the U. S. in 1870, that she had been a resident of New Jersey immediately prior to her institutionalization, and that she had borne two children, neither of whom were “living.” Years later she would recant this statement — at least one child was indeed still “living,” if only for a few more days.

For Florence, adoption was of course preferable to a life on the streets or in an orphanage or other state institution, but the matter was kept private both by societal stigma surrounding adoption and by the law. It permitted Florence La Badie, or her later publicists, to invent a past that could not easily be disproven.

[UPDATE: Birth, Biological Parents and Adoption.] Florence La Badie was born Florence Russ on April 27, 1888 in New York City. She was the second child of Horace Blancard Russ and Marie Chester Russ. Father Horace, a real estate agent in Manhattan, was descended from two prominent New York families. His father, Horace P. Russ (d. 1866), was a building contractor who had invented “the Russ pavement” in the mid-nineteenth century, paving lower Broadway from the Battery to Fourteenth Street. The Blancards, the family of his mother Louisa (d. 1870), were hoteliers who owned The Pavilion, a popular resort on Staten Island.

On September 14, 1890, Horace Russ died, age 41, at the Hotel Gladstone in Manhattan, of “a complication of diseases” (per The New York Times obituary, Sept. 15, 1890), leaving his wife Marie a widow and the two children, Florence and her older brother, Horace (born 1884), fatherless. Within a year of their father’s death, Marie Russ, apparently unwilling or incapable of caring for either child, gave both up for adoption: Horace by his father’s great-aunt, Louisa Blancard Marsh (d. 1901), and Florence by Joseph and Amanda La Badie.

* * *

When Florence (or studio publicists) told her story to the early film magazines between 1912 and 1914, she described her beginnings in show business on stage with Chauncey Olcott, the hugely popular Irish tenor from Buffalo, New York. Olcott was by far the leading figure in the late 19th-early 20th century wave of enthusiasm for Irish or Irish-flavored music and theater (which itself was based upon nostalgia for an idealized pre-famine life in Ireland that few remembered, if it ever existed in the first place). In addition to being the “silver-throated tenor,” Olcott was an actor, stage director, producer and songwriter, having penned melodies and lyrics which are, incredibly for music of its era, still remembered in the 21st century, among them most notably, “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” and “My Wild Irish Rose.”

When Florence (or studio publicists) told her story to the early film magazines between 1912 and 1914, she described her beginnings in show business on stage with Chauncey Olcott, the hugely popular Irish tenor from Buffalo, New York. Olcott was by far the leading figure in the late 19th-early 20th century wave of enthusiasm for Irish or Irish-flavored music and theater (which itself was based upon nostalgia for an idealized pre-famine life in Ireland that few remembered, if it ever existed in the first place). In addition to being the “silver-throated tenor,” Olcott was an actor, stage director, producer and songwriter, having penned melodies and lyrics which are, incredibly for music of its era, still remembered in the 21st century, among them most notably, “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” and “My Wild Irish Rose.”

Olcott, who changed his first name from Chancellor to “Chauncey” because it sounded more Irish, was based in Saratoga Springs, New York, and though he made yearly pilgrimages to Ireland, he spent more time on the road with his stage productions than in New York or Ireland combined. Olcott was now 50, and had spent nearly all his life on the musical stage in every town in North America that had one. (He told a humorous tale of an 1880s fair in Cheyenne, Wyoming in which he entered a footrace and outran a group of cowboys and an Indian, winning a $500 cash prize, only to be recognized later that night as he came onstage to sing. Thinking he was about to be exposed as a ringer and lynched, the cowpokes in the audience waited until he finished his number — then gave him a standing ovation.)

By 1908, Olcott had been a major star of the musical stage for more than two decades, typically playing swashbuckling, sword-carrying heroes. Now he was looking to produce something trendier without alienating his audience. The play that he chose was one written by Rida Johnson Young and Olcott’s wife and sometime lyricist, Rita Olcott. Ragged Robin was, as the press described, “a sort of Irish ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ with fairies playing almost as prominent parts as the human characters . . . a light pastoral play filled with folklore and Olcott songs.” (The Washington Post, Jan 19, 1909.) Cast as one of those “fairies” was twenty-year old Florence La Badie.

By 1908, Olcott had been a major star of the musical stage for more than two decades, typically playing swashbuckling, sword-carrying heroes. Now he was looking to produce something trendier without alienating his audience. The play that he chose was one written by Rida Johnson Young and Olcott’s wife and sometime lyricist, Rita Olcott. Ragged Robin was, as the press described, “a sort of Irish ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ with fairies playing almost as prominent parts as the human characters . . . a light pastoral play filled with folklore and Olcott songs.” (The Washington Post, Jan 19, 1909.) Cast as one of those “fairies” was twenty-year old Florence La Badie.

“Fairy plays” were in vogue at the time (see Peter Pan, or A Good Little Devil). La Badie, with little or no experience acting, was in all probability hired for Ragged Robin on the basis of her physical beauty, one that must have translated charismatically on stage. (And it appears that not all of the “fairies” had lines to speak, which could have made her theatrical début in such a role a bit less taxing.) However, what really makes the Olcott/Ragged Robin story more interesting is its connection with the person La Badie would later describe as the spark igniting her career in motion pictures, Mary Pickford:

“I posed for front covers of magazines before I went on the stage and afterward, between shows. That was what made me think I would fit into work for the screen. Mary Pickford is a dear friend of mine and it was Mary who suggested I try pictures.” “Sans Grease Paint and Wig,” By Mabel Condon, Motography, April 1914.

While I don’t doubt that by 1914 Florence La Badie considered Mary Pickford a dear friend, I’m less inclined to believe that La Badie had even a casual acquaintance with Pickford prior to April, 1909. Admittedly, this is an educated guess on my part. Despite the fact that both were touring onstage during the 1908-09 theatrical season, it is nearly impossible that their paths could have crossed until the Ragged Robin company wound its way back to New York in mid-April 1909 (you can verify this by comparing the 1908-09 tour schedules of Ragged Robin and The Warrens of Virginia, below). And even that is based on the assumption that La Badie was still with the production by that time.

The only evidence I’ve seen to connect La Badie with a specific performance during the Ragged Robin tour is a reference to an article in a 1914 issue of Motion Picture Magazine in which she is described as playing one of the fairies onstage at the Grand Opera House in Lexington, Kentucky the first week of October, 1908. It would have been unlikely that the New York native La Badie would have joined the show in Lexington — it is probable that she was hired and started out with the production at its August premier in Olcott’s home base in upstate New York, at Saratoga Springs. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to come across a complete cast listing for the 1908-09 season production of Ragged Robin. The play did not début on Broadway until its second season, in January, 1910 when Charlotte and Lottie Smith, the mother and sister of Mary Pickford, appeared in the cast credits in The New York Dramatic Mirror. But we know that the Smiths were also in the first season road company of Ragged Robin when it reopened after Olcott’s hiatus for lent, at the Majestic Theatre in Brooklyn on April 5, 1909.

The Smiths had a history with Chauncey Olcott that predated both Ragged Robin and Florence La Badie. In 1905, mother Charlotte, sister Lottie and brother Jack along with sister Gladys, had roles, including at least one song in Olcott’s production, Edmund Burke. Changing their names to Milbourne-Smith to add just a touch of respectability, the Smith family played with Olcott an entire season. A couple of seasons later, he hadn’t forgotten them, and cast two of them in Ragged Robin, Lottie as the sister of the leading lady and Charlotte in a smaller, supporting role. Gladys, however, had already been hired by David Belasco for his extravagant production of the Civil War drama, The Warrens of Virginia. Gladys, now rechristened “Mary Pickford” by Belasco, began a national tour with The Warrens in December, 1907. The Warrens, with Mary Pickford, returned for the 1908-09 season in September, and closed at the West End Theater in New York on March 20, 1909.

All four Smiths were back in New York by late March 1909. While Mary was “between engagements,” her mother and sister were in Brooklyn for the beginning of the final leg of the Ragged Robin tour. And it was at the Majestic Theatre on a Monday evening, April 19, 1909, that Mary Pickford may well have given Florence La Badie the suggestion that she “try pictures.”

* * *

Chauncey Olcott production, “Ragged Robin,” 1908-09 Season: (Opening) Aug 14-15, Saratoga Springs, NY, Broadway Theatre; Aug 23-29, Minneapolis, MN; Aug 30-Sep 5, St. Paul, MN; Sep 8-10, Duluth, MN; Sep 11, Red Wing, MN; Sep 12, Winona, WI; Sep 14, Lacrosse WI, The Lacrosse Theatre; Sep 16, Sioux Falls, SD; Sep 17, Sioux City, IA; Sep 18, Omaha, NB; Sep 19, St. Joseph, MO; Sep 20-26, Kansas City, MO; Oct 6-8, Lexington, KY, Grand Opera House; Oct 9, Richmond, IN; Oct 10, Indianapolis, IN; Oct 11-31, Chicago; Nov 1-7, Detroit, MI; Nov 9, Jackson, MI; Nov 10, Battle Creek, MI; Nov 11, South Bend, IN; Nov 12, Kalamazoo, MI; Nov 13, Grand Rapids, MI; Nov 14, Lansing, MI; Nov 16, Saginaw, MI; Nov 17, Bay City, MI; Nov 18, Pt. Huron, MI; Nov 19, London, Ontario, Canada; Nov 20-21, Hamilton, Ontario; Nov 23-25, Toronto; Nov 26, Erie, PA; Nov 27, Jamestown, NY; Nov 28, Niagara Falls, Ontario; Nov 30, Syracuse, NY, The Wieting; Dec 1, Auburn, NY; Dec 2, Rochester, NY; Dec 3-5, Buffalo, NY; Dec 7-12, Jersey City, NJ; Dec 14, Roanoke, VA; Dec 15, Lynchburg, VA; Dec 16-17, Norfolk, VA; Dec 18-19, Richmond, VA; Dec 21-Jan 9, Philadelphia, PA; Jan 11-16, Pittsburgh, PA; Jan 18-23, Washington, DC, The Columbia; Jan 25-30, Baltimore, MD; Feb 1-6, Brooklyn, Broadway Theatre; Feb 8-13, Newark, NJ; Feb 15, Middletown, NY; Feb 16, Newburgh, NY; Feb 17, Poughkeepsie, NY; Feb 18, Troy, NY; Feb 19, Schenectady, NY; Feb 20, Albany, NY; Feb 22, Utica, NY; Feb 23, Oswego, NY; Feb 24, Watertown, NY; Feb 25, Rome, NY; Feb 26, Glens Falls, NY; Feb 27, Bennington, VT; [Olcott on hiatus for Lent]; Apr 5-24, Brooklyn, NY, The Majestic; Apr 26, Danbury, CT; Apr 27, Bridgeport, CT; Apr 28, Waterbury, Ct; Apr 29, New Haven, CT; Apr 30, New Britain, CT; May 3-22, Boston, MA (Closing).

David Belasco production, “The Warrens of Virginia,” 1908-09 (2nd) Season: (Opening) Sep 21-Oct 3, Boston, MA; Oct 5-7, New Haven, CT; Oct 8-10, Providence, RI; Oct 12-17, New York City; Oct 19-24, Brooklyn, NY, Majestic Theater; Oct 26-Nov 7, Philadelphia, PA; Nov 9-14, Baltimore, MD; Nov 16-21, Washington, DC; Nov 23-28, Pittsburgh, PA; Nov 29-Dec 5, Cincinnati, OH; Dec 7-9, Indianapolis, IN; Dec 11, Vincennes, IN; Dec 12, Belleville, IL; Dec 13-19, St. Louis, MO; Dec 28-Jan 9, New York City; Jan 11-16, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Jan 18-23, Buffalo, NY; Jan 25-30, Cleveland, OH; Feb 4-6, Milwaukee, WI; Feb 11-13, Omaha, NB; Feb 14-20, Kansas City, MO; Feb 21-Mar 6, Chicago, IL; Mar 9-10, Toledo, OH; Mar 15-20, New York City (Closing).

Just a casual glance at these tour schedules shows the contrast between the Belasco production, which tended to remain for multiple dates in the larger cities, and Olcott’s production which stopped for one-nighters at numerous medium and small cities, particularly in the Midwest and upstate New York, areas of particularly intense Olcott fandom. However, several large metropolitan areas, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston and Brooklyn, were considered the heart of his fan base. Ragged Robin spent three weeks each in Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston, and appeared twice in Brooklyn, including the three-week stand in April, 1909, where Pickford and La Badie may have crossed paths. (Tour dates are culled from the “Dates Ahead” listings in the weekly theater periodical The New York Dramatic Mirror from August 1908 through May 1909.)

* * *

During the years when Florence La Badie would have been attending school (a girls school in Montreal or high school in Manhattan) and working as an artist’s model, Mary Pickford, though four years younger, was already a seasoned stage performer. She had been a working professional actor since 1899 when she became her fatherless family’s primary source of income at the age of seven. The Smiths’ first gig with Chauncey Olcott in 1905 was a definite step up the theatrical ladder. But it was in Belasco’s The Warrens of Virginia that Gladys Smith landed an important supporting role, acquired a new stage name and reached her goal of becoming a success on Broadway. It was, therefore, all the more discouraging that upon the closing of Warrens, while her mother and sister were still appearing with Olcott, that mother Charlotte suggested she seek work in the moving pictures at Biograph. And on that stormy Monday evening in New York, after a horrendous but profitable day with Griffith at Biograph, Mary Pickford, still drenched and clutching her day’s pay, an equally soaked five dollar bill, may have encountered backstage one of Olcott’s fairies, Florence La Badie.

Ragged Robin left Brooklyn at the end of April to finish the season with a swing through Connecticut, then a three-week stand at Boston, closing on May 22nd. During that time, Mary Pickford made nearly a dozen Biograph shorts directed by Griffith, in parts ranging from bits to leads. Her brother Jack appeared as an extra in one film and sister Lottie had a bit part in another. La Badie told later interviewers that she accompanied her friend Mary Pickford to the Biograph studio one morning in mid-1909. This is plausible and we have no strong reason to doubt it, although a reference La Badie made in a 1914 interview for Photoplay Magazine to “the very first time I worked before the camera three years ago at the Biograph studio” makes one question it — or her memory. Or is it possible that it was so insignificant that she never considered this her “start” in motion pictures? It is worth noting that Pickford was not in favor of her younger sister entering films, and said as much to a co-worker at the studio (“She confided that Lottie was not pretty and she didn’t think she’d be good in the movies,” according to Mrs. Griffith, Linda Arvidson). Pickford may not have had the same sort of reservations concerning a job referral for an acquaintance, La Badie, whose arresting good looks would at least give her an opportunity to obtain work — and even a reasonable chance of success — in silent film.

On her first day accompanying Pickford to Biograph, La Badie claimed to have gotten work as an extra in the film, Getting Even. Shot during three days in early August, 1909, at the Biograph studio and in the town of Edgewater, New Jersey, Getting Even was released on September 13th. A split-reel comedy with Billy Quirk in the lead, Mary Pickford is little more than eye candy in the opening and closing scenes. The only scene in which other females appear is during the ballroom sequence, where a number of actresses (including Lottie Pickford) serve as extras. But Florence La Badie is not discernible in the available footage of Getting Even. (In my copy, neither is Lottie Pickford!) The studies by the authors of “D. W. Griffith and the Biograph Co.” and the contributors to “The Griffith Project” (see the Sources at the end of this article), having access to better viewing copies of the film plus the notes of Biograph cameraman Billy Bitzer, do not find La Badie in the film. Of course, it’s always possible she ended up on the cutting-room floor.

The second film mentioned in the early experience of Florence La Badie is In the Window Recess, a split-reel drama, shot during mid-October. Only 337 feet in length (well under ten minutes), a format usually reserved for physical comedies, In the Window Recess was paired on the same reel with a longer film, A Trick that Failed, a situation comedy featuring Mary Pickford in the lead. In the Window Recess, a brief suspense thriller with Marion Leonard, had a small cast with no extras. But it had two bit parts, “Callers” to Leonard’s home, and only one has been positively identified (as Biograph regular Jeannie MacPherson). I don’t have access to a copy of the film, but I would think that La Badie would be recognizable if appearing in a sparsely populated drawing-room scene. Again, she may have been edited out of the finished film released November 29, 1909.

At this early point in her career, Florence La Badie was very much a novice. Without having significant stage or film experience, it was next to impossible for her to crack the Biograph company of regulars in 1909. The pace was brutal, averaging two films released per week, with at least three or four more films in various stages of production at any given point on the calendar. Biograph had just divested itself of the services of Florence Lawrence. Now, the experienced stage and film actress Marion Leonard and the promising newcomer Pickford were expected to pick up the slack. At Biograph, even the leads played bits and extras (as scene “decorations,” per Linda Arvidson). Florence La Badie likely realized that a film career would require more on a résumé than “artist’s model.” She returned to the stage in 1910, but not until the Fall.

Florence La Badie does appear in the 1910 U. S. Federal Census, living with her parents, Joseph E. and Amanda La Padi [sic, the name is variously spelled La Padi, La Badi, La Badie, or Labadie on official documents], both recorded as age 45. Daughter Florence, an only child, is listed, curiously, as age 19 on her last birthday (it had been 19 years since her adoption). The family resided in an apartment building at 557 West 124th Street. That street address in Morningside Heights, along with the entire street block, no longer exists — it is now part of Columbia University campus and housing. In 1910, the neighborhood was growing, with new apartment houses in the Italianate style, and with the extension of mass transit to the Upper West Side, it became a neighborhood convenient for office and professional workers who commuted to Mid-town and Downtown Manhattan. Among them Florence’s father, Joseph, who was employed as “real estate – broker.” Florence and her mother’s occupation? “None.”

Florence La Badie nearly disappears for much of 1910, at least as far as her career in show business is concerned. She may have continued to model. Linda Arvidson, in her memoir of the Biograph years “When the Movies Were Young,” locates Florence La Badie at the Biograph studio somewhat vaguely in the fall of 1910, noting “beautiful Florence LaBadie [sic]” as being among the new players to have “joined Biograph this season,” and recounts briefly the rise of La Badie to later stardom with Thanhouser. She notes that La Badie was “also in our California cast” for the second trip west in early 1911.

But in the Fall of 1910, La Badie had landed a small role in the Lee and J.J. Schubert production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird. On opening night on Broadway at the New Theater, October 1, 1910, she is listed in the cast as one of the “Hours, Mist Maidens and Stars” in The New York Dramatic Mirror of October 5, 1910. Although not specifically mentioning La Badie’s performance in a bit part, the Dramatic Mirror gave the production a rave review. (Appearing in one of the lead roles was fourteen-year-old Gladys Hulette. Already a veteran of the stage –most notably in A Doll’s House with Alla Nazimova — and a pioneering film actress with Vitagraph, Hulette would join Florence La Badie as a co-worker at Thanhouser in 1915.) Opening on Broadway without an out-of-town tryout period, The Blue Bird was a hit and ran for nearly four months. It moved to the Majestic Theatre on November 8, and continued until January 21, 1911.

Yet in January of 1911, we know that D. W. Griffith and the Biograph company made their second annual excursion to Southern California. They began shooting in Los Angeles January 5, and Linda Arvidson counts La Badie as a member of the company in California. Fortunately, this is where the loose strands of the Pickford/La Badie/Biograph connection start to come together. According to Florence La Badie:

“‘I went into this work just by accident,’ she said. ‘I was playing ‘Light’ in The Blue Bird, as a preliminary trial for a road company, at the New Theatre, and one day I went down to see Mary Pickford, an intimate friend of mine, and met Mr. Griffith, the director of the Biograph Company. In a day or two I was on my way to California as a regular member of the Biograph forces. [I spent] one season with the American [Biograph].” Photoplay Magazine, October 1912.

This single paragraph quote tells us much. La Badie was still with The Blue Bird company when she met with Pickford and Griffith. The meeting must have taken place no later than the end of December, before Griffith left for California. Pickford was no longer employed by Biograph. Her farewell party had taken place several weeks earlier. La Badie may have merely intended to meet Pickford for a casual visit and one thing led to another — a meeting with Griffith — and La Badie makes it sound as if she had not previously met the Biograph director. Equally interesting is that she says she “was playing ‘Light’ in The Blue Bird, as a preliminary trial for a road company.”

In the current Broadway production of The Blue Bird, La Badie was playing essentially a bit part. However, “Light” was a significant character in the play, and apparently La Badie was auditioning for this more important role with the intention of playing it in the road production. She is now confronted with an offer from D. W. Griffith — a very attractive and potentially more lucrative opportunity — in sunny Southern California, no less. It must have seemed far preferable to the prospect of another road tour grind, especially one beginning in the Northeast in January. It was probably not a difficult decision.

La Badie states that “In a day or two [after the meeting with Griffith] I was on my way to California.” While she certainly could have left The Blue Bird company early, before it closed, it would not explain why she did not make her first appearance in a Biograph film until early February. I believe she must have reached an agreement with Griffith that she would meet the company in California after The Blue Bird closed in New York. This fits with the historical evidence: two weeks after it closed, La Badie made her first documented appearance before the Biograph camera in Los Angeles. I doubt that she arrived earlier, then sat idly in Los Angeles the entire month of January waiting for a part, drawing a weekly salary for nothing. It is quite likely that she was employed immediately upon her arrival. After all, there was plenty of work and big shoes to fill.

By the beginning of 1911, Biograph had been stripped of several important players by the independent film companies, the most significant being the departure of Mary Pickford in December 1910. Griffith had invited a larger group of newer players into his company of actors than at any previous point, and was giving veterans like Claire McDowell and Dorothy West the chance to play more leads. La Badie’s chances of sticking with the company were certainly better than in 1909, but she had tremendous competition. In addition to West and McDowell, Blanche Sweet, Mabel Normand and Vivian Prescott were among the other actresses being given the opportunity to play leading roles as the Biograph company settled into their new, open-air studio in Los Angeles.

* * *

Southern California was ideal for exotic themes — the ocean, old Mexico and “Spanish Gypsies” being favorites of Griffith when in California. And it was as a “Spanish Gypsy” that Florence La Badie made her documented debut with Biograph the first week of February, 1911. The Spanish Gypsy, a single reel drama released at the end of March, was merely another bit part for La Badie, an extra in extravagant costume. But the second film in which she appeared would give Florence La Badie her first lead role in a moving picture.

The Broken Cross , shot the second week of February and released April 6, 1911, was not a religious film, but rather a reworking of the theme of young love separated by distance and threatened by temptation found in Griffith’s earlier effort, The Broken Locket (1909), with Frank Powell and Mary Pickford. Unlike that couple, torn apart by the moral failings of Powell’s alcoholic character, the rural sweethearts of The Broken Cross, exchanging halves of that talisman, are able to weather the temptations that the country boy (Charles West) encounters in the big city –this time played for comedy. A sexy “manicurist” (Dorothy West) takes a liking to the boy and attempts to deceive him by forging a letter from his sweetheart (Florence La Badie) supposedly ending their relationship — the manicurist encloses the other half of the broken crucifix, which she has also faked. The boy finds the fake and returns to his girl back home.

Dorothy West and Vivian Prescott (as a waitress) get the showy comic parts. Film historian Kristin Thompson explains that Florence La Badie does some convincing work despite the restrictions of her vanilla character:

“Florence La Badie has the rather thankless task of carrying the country scenes alone . . . gazing out a window or visiting the mailbox hoping for news. She does perform two nice bits of typically Griffithian business that add some poignancy to her situation. One could easily imagine Lillian Gish drawing such comic or poignant gestures in one of the [later Griffith] features.” (Kristin Thompson, contributor, The Griffith Project, “The Broken Cross.”)

In addition to Thompson’s comments on the film, The Broken Cross has received attention from other scholars of early film and film acting. Scott Simmon, in his classic work, “The Films of D. W. Griffith,” and Roberta Pearson in her groundbreaking study of early film acting, “Eloquent Gestures,” both use The Broken Cross as an example of Griffith’s use of contrasting styles of acting to emphasize the differences between characters and lifestyles, comparing the small, restrained gestures of the “country” sweethearts, La Badie and Charles West, with the exaggerated ones of the conniving city girls, the manicurist and the waitress played by Dorothy West and Vivian Prescott.

Her next two Biograph appearances are examples of the rotation of parts among Griffith’s “stock company,” as Florence La Badie, despite her promising work in The Broken Cross, is given a supporting role as an “Angel” in Paradise Lost and as an extra in A Knight of the Road. Paradise Lost, shot in mid-February and released two months later, is a one reel situation comedy produced by the unofficial “second unit” of Biograph, directed not by Griffith, but by either Frank Powell (who had become Griffith’s assistant in addition to his actor’s duties) or Mack Sennett, who generally handled the comedy shorts at Biograph at this stage (though he would shortly strike out on his own.) Sennett plays the lead, a drunk who is tricked into believing he has died after a bender, and two maids dressed as Angels (played by La Badie and Vivian Prescott) are employed to add “realism” to the ruse.

In A Knight of the Road, also shot in mid-February, released late in April, and one of Griffith’s better-regarded 1911 California films, La Badie is merely an extra in the kitchen of a wealthy estate.

When Florence La Badie gets her next shot at a leading role, it is in the split reel comedy, Dave’s Love Affair, directed by Sennett, paired on the same reel with a second Sennett short, Their Fates Sealed. Unfortunately (and unlike most Biographs of the period), both films are lost. However, in the case of Dave’s Love Affair, the photograph accompanying the Biograph advertisement, published in The New York Dramatic Mirror on June 7, 1911, shows Eddie Dillon as “Dave” and Florence La Badie as his love, “May.”

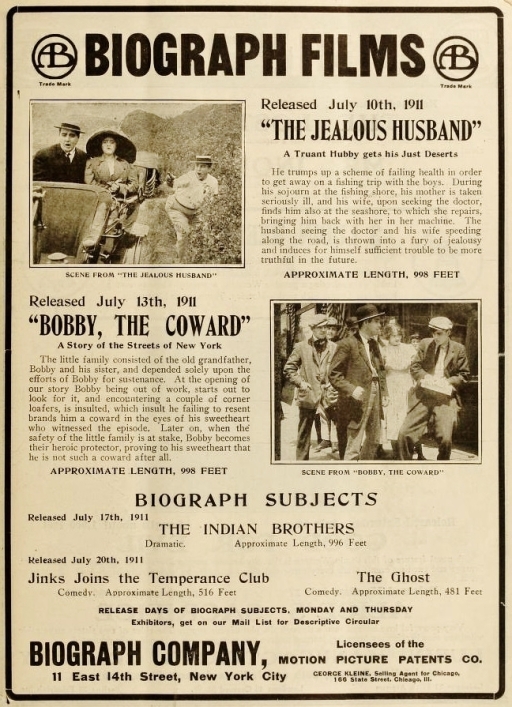

Enoch Arden was, for Griffith and Biograph, a groundbreaking film. Intended by Griffith to be the first Biograph to break the one-reel barrier, the company insisted that its two reels were released separately, three days apart on June 12 and 15, 1911. But Biograph was already behind the curve — domestic producers had begun releasing two-reelers and Italian producers were making films in excess of five reels, films that would shortly be imported to the U. S. by distributor George Kleine of Chicago. As can be seen in the Biograph Ads, George Kleine was distributor for the Biograph product in the Midwestern U. S. (but apparently had no influence over the Biograph handling of Enoch Arden Part One and Two).

Enoch Arden was based on the Tennyson poem of a shipwrecked sailor separated by an ocean from his wife and family patiently hoping for his return. Florence La Badie portrayed one of Enoch’s two children (the other played by Bobby Harron), mere babes in Part One, who had now grown into their teens without their father in Part Two.

La Badie would next have a small role in another film, well-regarded at the time, Fighting Blood, a precursor to the violent “whites-attacked-by-savage-natives” western subgenre best exemplified by the more ambitious two-reel The Battle of Elderbush Gulch a year later. Florence La Badie, seen just right of center, below, has a small role (appearing in two scenes) as the female friend of the young man who bristles at his father’s militaristic approach to child-rearing.

Among the last Biographs shot in California in 1911, the first week of May, and released the same week in July as Fighting Blood, Her Sacrifice had Florence La Badie as the girl betrothed in an arranged marriage to the son of a wealthy Mexican landowner. However, it was Vivian Prescott as his true love, a lowly barmaid, who apparently had the meatier role and walked off with the acting honors, according to at least one reviewer of the period: “The acting of the girl of the inn is especially good,” (The New York Dramatic Mirror, July 5, 1911.)

In The Thief and the Girl, La Badie plays a girl who dissuades a thief — a man she recently met and befriended in the park — from burglarizing, unwittingly, her own house! A light-hearted warm-up for Griffith’s dark and dismal The Painted Lady with Blanche Sweet the following year, viewing copies of The Thief and the Girl are not yet available, but the cast and synopsis are documented by the reviews and the Biograph ad, with accompanying photo, reproduced here from The Moving Picture World of July 8, 1911.

* * *

When the Biograph company returned from California at the end of May, Florence La Badie was cast in a tale of the mean streets of the Lower East Side. This wasn’t some sort of historical recreation, but the real thing, serving as the milieu for the tale of a young man who supports his family, but who is torn between responsibility and peer pressure by the gangs who run the streets. Bobby, The Coward gave Florence La Badie a small but important role as his girlfriend who thinks him a coward for not retaliating in kind when he is insulted by the gang of young criminals.

Bobby, The Coward may have been the film that caught the attention of her next employer. A Thanhouser executive supposedly saw La Badie in a Biograph film shortly after she had appeared at the company looking for a position. Evidently, she saw the independent Thanhouser as an opportunity to better display her talents and simultaneously earn the public recognition that she would not get from Biograph with its policy of anonymity regarding their players. It was a wise move. Soon, La Badie would be followed at the Biograph exit by others, including Mabel Normand (with Sennett) and Vivian Prescott (to the I.M.P. Company), then in less than two years, Griffith, taking with him many of Biograph’s most talented players, including Blanche Sweet and Lillian Gish.

* * *

[To be continued in PART TWO: Thanhouser and stardom.]

FLORENCE LA BADIE, Biograph Filmography (by release date): [All films were shot in California at the Los Angeles studio or on location, except Bobby the Coward, made at the Biograph Studio and on location in New York City. All were one reel films, except Dave’s Love Affair, a 600 foot, “split reel” comedy.]:

The Spanish Gypsy, March 30, 1911, dir. D. W. Griffith, (As one of seven “Gypsies,” bit);

The Broken Cross, April 6, 1911, dir. Griffith, (“Kate,” a lead role);

Paradise Lost, April 13, 1911, dir. Mack Sennett or Frank Powell, (One of two “Angels”);

A Knight of the Road, April 20, 1911, dir. Griffith, (“in the Kitchen,” a bit);

The New Dress, May 15, 1911, dir. Griffith, (“at Wedding,” a bit);

Dave’s Love Affair, June 8, 1911, dir. Mack Sennett, (As “May,” a lead role);

Enoch Arden, Part Two, June 15, 1911, dir. Griffith, (Enoch’s “child as a teenager”);

The Primal Call, June 22, 1911, dir. Griffith, (a “Servant”);

Her Sacrifice, June 26, 1911, dir. Griffith, (the “Son’s sweetheart”);

Fighting Blood, June 29, 1911, dir. Griffith (the “Son’s friend”);

The Thief and the Girl, July 6, 1911, dir. Griffith, (“The Girl”);

Bobby the Coward, July 13, 1911, dir. Griffith, (“The Girl next door”).

Primary sources:

Public Records: 1900 United States Federal Census; 1910 U. S. Federal Census; New York City Marriages, 1600s – 1800s; U. S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992; and the Blancard and Russ family trees; (all via Ancestry.com); The New York Times, Horace B. Russ obituary, published September 15, 1890.

The Internet Archive (internetarchive.org) at The Media History Digital Library (mediahistoryproject.org) for The Moving Picture World, Photoplay Magazine, Moving Picture Story Magazine and Motography.

Archives of The New York Dramatic Mirror at fultonhistory.com, for The New York Dramatic Mirror.

The Washington Post, via newspaperarchive.com.

Secondary sources:

Usai, Paolo Cherchi, General Editor, “The Griffith Project, Volume 3, Films Produced in July – December 1909,” BFI Publishing, 1999; “The Griffith Project, Volume 5, Films Produced in 1911,” BFI Publishing, 2001;

Cooper C. Graham, Steven Higgins, Elaine Mancini, Joao Luiz Vieira, “D. W. Griffith and the Biograph Company,” The Scarcrow Press, Inc. (1985);

Griffith, Mrs. (Linda Arvidson), “When the Movies Were Young,” E.P. Dutton and Co., 1925;

Scott Simmon, “The Films of D. W. Griffith,” Cambridge University Press (1993, 1998 paperback).

Mary Pickford, “Sunshine and Shadow,” Doubleday, 1954;

Whitfield, Eileen, “Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood,” University Press of Kentucky, 2007, paperback;

Broadway theater names, dates and cast listings via ibdb.com.

Photos (excluding those reproduced from original source periodicals credited above):

Florence La Badie (on sofa, main text) and both Chauncey Olcott photos, nypl.org, The Billy Rose Theater Collection. 574 West 124th Street c. 1925, Museum of the City of New York Collections (mcny.org);

Still frames from Getting Even, from “The Biograph Series, D. W. Griffith Director, Vol. 4 (1909),” Grapevine Video DVD (2006); Enoch Arden, Part Two, from “Griffith Masterworks, Biograph Shorts, Special Edition,” KINO Video DVD (2002). Still frame from Fighting Blood, via YouTube at http://bit.ly/13tFdIf .

The following two websites are excellent sources of information on the life and later career of Florence La Badie:

http://www.thanhouser.org/index.html

http://www.lilaclane.com/florence-labadie/biografy.htm

It is always fascinating to learn about florence la badie, my favorite silent film actress. I cant wait to read the second part.

I’m glad you liked it. Working on “Part Two.” I appreciate your comments and your interest in the subject as well!

I am curious to read your part two since your part one is quite acccurate and well written.

I am a relative of FLorence Labadie and still working on some secrets…

I am looking for birth certificate, will, adoption papers and the declaration of her birth mother about the fact that florence is her daughter..Yes she was adopted and I can confirm that her mother was married she also had a brother the father died in 1890 and the mother went to hospital prior to 1900….at a certain date unknown. In 1920 she was still living in that hospital. I have some family letters that permit me to confirm some few facts but not ready to bring anything out yet.

lise

Lise,

I’m always amazed (and pleased) when I hear from relatives of the people of whom I’ve written. I try to bring to the general audience accurate accounts and informed opinion of the lives of figures in the performing arts who have been overlooked, forgotten or misunderstood. I find Florence La Badie, her life and career to be a fascinating chapter in early film, but I’m not attempting anything close to a biography — more of a biographical sketch, in reality.

My account of her early life, i.e., her birth and adoption and family information, came from one primary source, Ancestry.com, and two secondary sources that are available on the internet that you probably have already found, http://www.lilaclane.com/florence-labadie/biografy.htm, and via the Thanhouser website at http://www.thanhouser.org/tcocd/Biography_Files/indfdkind.htm.

Also, Ned Thanhouser has indicated (at the Nitrateville website) that he has a copy of the Marie Russ letter from 1917: http://nitrateville.com/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=15706#p117830.

The remainder of my article, dealing with her early career was based upon primary contemporary (1908-1911) news media sources.

The author of the “lilaclane.com” article, Bryan Smith, appears to have researched and discovered the existence of the adoption records, although it is not clear from his article whether he actually examined the original records (or copies) or if he received this information from another, secondary source. As a relative, you should be able to find this information from the City of New York, or the State, assuming you haven’t already attempted this.

Please let me know, at least in general terms, what you find in your research. I plan on examining her career, i.e., her films post-Biograph in the next installment, which I’ve only had the chance to work on sporadically. If you would like to contact me privately, send me an email at: zonarg@aol.com.

Thanks (and thanks for commenting, as well),

Gene.

“…it gave her the possibilities in life otherwise virtually beyond the reach of a poor, bastard child in a late 19th century urban environment.” I don’t mean to be picky or negative about your wonderful blog, but I wanted to point out that Florence was not a “bastard”. Her parents were married, as Florence’s relative Lise points out. Florence’s father died from tuberculosis in 1890. He is buried (unmarked) near Florence in the Russ burial plot. Source: Green-Wood cemetery archives. It would make sense that his death was the reason that Florence and her brother were given up for adoption in 1891. Florence’s widowed mother was unable to take care of her.

I hope you get part 2 done soon, What a great job you did with part 1 !!

Paul,

Thanks for commenting and kind words. Yes, Florence was not born out of wedlock, but to parents who were hardly poor — her father came from a prominent NYC family. I didn’t update my original article which was written before I collaborated with Lise on researching the Labadie and Russ family histories. I planned on including the new information on the early life story of Florence in follow-up articles and will do so when I am able to, hopefully in the near future.

Gene.

Paul,

See the “Updated” birth, family, adoption information, now included in the article.

Gene.

Your essay on Florence is truly an early Christmas present for me! You’ve done some very sharp thinking about the contours of her early career with Biograph and I appreciate the reference to the lilaclane site. In the late 80s and early 90s, I did a good deal of research at the Academy Library in LA and was able to dig up some information about the adoption by contacting the NYC Dept of Public Records. Believe it or not, in those long ago days, someone actually answered the phone there and they sent a confirmation that Florence had been adopted by the Labadies in 1891 — not the full documentation because that was still sealed despite the passage of a century but at least official recognition of the event.

I put together the article on the site back in 1992 and added a few updates in 1998; with the help of my much more internet savvy wife, there are now links to some of the tributes that have appeared in recent years. Obviously, we’ll have to add your site! It’s been wonderful to see the work Ned Thanhouser has done restoring so many of his grandfather’s productions. Before there’d been a handful of the Biographs and a few Thanhousers in which Florence could be appreciated but now so much more — although it’s hard not to be greedy and hope for a few MIllion Dollar Mystery episodes! Also great to see those affectionate tributes though troubling that some uncritically accept the bizarre misinformation concocted by an author named Charles Foster in his book entitled “Stardust and Shadows” that contains a FLB article. I’ve been working on a — hopefully! — brief rejoinder with a list of the many errors and fantastic assertions that I’ll post on our site. Well, enough negativity. I certainly look forward to Part 2 of your essay and any revelations that may come from Lise (comment above) — most of all, of course, to the long-awaited memorial on Florence’s gravesite mext year!

GENE

has sent me connection to your comments thank you and thanks to Gene..With whom I have been exchanging in private….Soon the picture on Florence will be more accurate and better informed. There are informations we are still missing so we can understand why she was buried in the russ family plot..and it is; 1.-what is the real name of the mother marie c. and her parents this could be found in the original marriage record at the state and not in ancestry where it is not clear.

2.-Who signed the adoption paper..could it be the same judge HE WAS FROM NEW JERSEY who also signed the piece where marie her natural mother says that her daughter Florence will probably be buried in the russ family plot.

He signed above the signature of marie c. which seems to be a little akward.

Was he a friend of the van vleck of the jessie blancard olstrom. both natural aunts of Florence.

Bryan,

Thanks for the compliments — your prior work on Florence La Badie was inspiring and, along with the information available on the Thanhouser website, gave me the basis to explore her early life and the beginnings of her career. My next essay will look at her film career in the months following her departure from Biograph and the early period of her work with Thanhouser leading to stardom with that firm.

I’ve been debating whether or not to address directly or indirectly what you aptly label the “bizarre misinformation” on Florence La Badie. Like you, I abhor the idiotic fantasies about her that appear to have as their source a God-awful book about Canadian silent film stars that relies upon nothing more than the supposed “memories” of the purported “author,” a retired actor whose book is based upon gossip, innuendo and

casual “conversations’ he allegedly had with assorted acquaintances seventy years ago. If he is not directly responsible for writing this trash, then at best he was an unfortunate dupe. It is ironic in that Florence was not a native of Canada, but born in America, a New Yorker who lived in the city most of her brief life. But that is the only excusable fault of this vile volume.

I realize that by even mentioning this, I may pique the interest of those unaware of it — that is why I planned on ignoring it, as had you and Thanhouser. But I think you should go ahead and do a piece to refute the rumors, and I look forward to it. Idle fantasy should not go unchallenged and allowed to stand and become accepted as “fact.” The real story of Florence La Badie is fascinating, genuinely heartbreaking, and deserves to be told truthfully, in its entirety.

LISE has been working on uncovering her roots, the mysteries of her very early life, and how she came to rest in the Russ family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. I have been assisting her, but privately, and because she is a relative of Florence, I will respect her wishes as to how and when she reveals the results of her investigations.

Gene — Thanks for the kind words. I soon hope to have a worthwhile rebuttal to what you rightly call fantasy; may I email it to you for your thoughts before going public? Amazing to hear of a Florence relative and good to know you’re working with her — there’s much to look forward to!

Bryan,

You’re welcome. Yes, I’d love to see your rebuttal before you release it. Please email it to:

zonarg@aol.com.

Lise has been researching family records, both biological and adoptive families, with my occasional assistance, and there is some interesting information being gathered to fill in some of the blanks, but I’ll defer to her wishes as to when or how this information is revealed.

Gene.

Hello, do you know when the second part of Florence La Badie becoming will be posted?

Suil,

I’ve done much of the basic research, but haven’t yet gotten around to writing it. Thanks for your interest.

Gene.