“It has long been a source of wonder to me that many women have not seized upon the wonderful opportunities offered to them by the motion picture art to make their way to fame and fortune as producers of photodramas. Of all the arts there is probably none in which they can make such splendid use of talents so much more natural to a woman than to a man and so necessary to its perfection.” “Woman’s Place in Photoplay Production, By Madame Alice Blache,” The Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914.

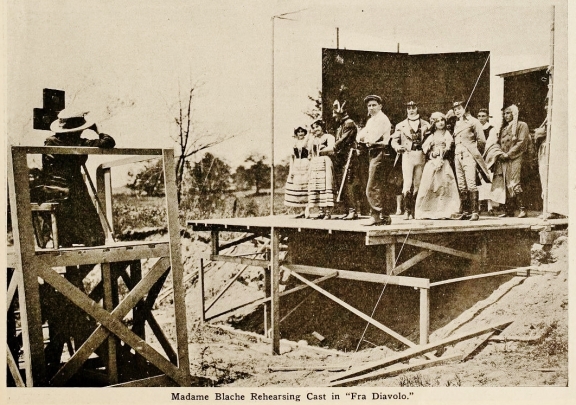

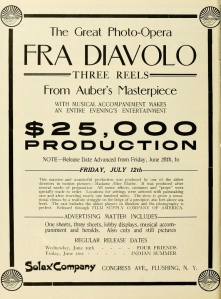

Alice Guy-Blache (at far left) and the cast of Fra Diavolo (Solax, 1912) a three-reel feature film, the first released by Blache’s Solax Studio. Both Blache and independent filmmaker Helen Gardner (Cleopatra, Helen Gardner Picture Players, 1912) were producing and directing feature-length films in America in 1912, preceding by nearly two years the first such effort by D. W. Griffith (Judith of Bethulia, completed 1913, released 1914).

[NOTE: A documentary film project, Be Natural: The untold story of Alice Guy-Blache, by Pamela Green and Jarik van Sluijs, is currently the subject of a Kickstarter fund-raising drive that ends at 2:59 AM EDT, Tuesday, August 27, 2013. Please check out the fantastic trailer for the project at the Kickstarter website, and consider becoming a backer of this worthy endeavor. Then read the rest of this post! More information on Madame Blache can also be found at selected links that I’ve included at the bottom of this article. Thank you kindly.]

Alice Guy-Blache was a pioneer filmmaker who as much as anyone created the narrative or “story” film, a decade before such films began to dominate film production. Working first in France with Gaumont, she founded her own film studio in America, and was a major player among the independent filmmakers, as well as an early proponent of feature-length films. Yet Alice Guy-Blache has been largely overlooked by nearly all except those who take a special interest in early film and filmmaking. She is unknown to the general public and was forgotten more than seven decades ago by the film industry she helped create.

In most histories, Blache is usually ignored or, if mentioned at all, only as a token; because of her gender, an oddity. Blache has been absent from the histories for three primary reasons. One, she was a small, independent producer, one of many who were unable to stay in business when film production — once a cottage industry — became big business as mergers created large corporations, combining production, distribution and exhibition, all backed by financial interests in New York. Two, when sound replaced silent film, the work of Blache and her contemporaries, big and small, was relegated to the dustbin of popular culture, a quaint artifact to elicit smiles or smirks, kept alive by nostalgia merchants and film obsessives.

The third, and most insidious reason for the disappearance of Alice Guy-Blache from the story of film can be traced to the beginning of “film history,” and the first comprehensive study of the development of motion pictures. In late 1920, Terry Ramsaye, a journalist working within the film industry, was commissioned by Photoplay Magazine to write a series of articles documenting the development — “the rise” — of motion pictures. What was originally intended as a series of twelve articles published in monthly installments became a thirty-six part series, ultimately published in a 900 page, two-volume work, A Million and One Nights, A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925 (Simon and Schuster, 1926). Although Ramsaye took particular pains to stress that he had severed all corporate connections with the industry and wrote not on “behalf of any person or concern in anywise related to the art or industry,” the first edition of “A Million and One Nights” was signed and prefaced by no less than Thomas Alva Edison, the self-proclaimed creator of the art and the industry of motion pictures.

Ramsaye’s work set the stage for years of “histories” to come by emphasizing American film, de-emphasizing the work of the French, and building his story through the works of the dominant U. S. companies, Edison and Biograph. (For historians, this was the peak of the “Great Man” theory of history, wherein the story of humankind could best be told through the stories of “great men.” Edison and Griffith certainly qualified. Alice Guy-Blache did not.) Although the independent filmmakers were not completely ignored by Ramsaye, those he included were used primarily to illustrate a tale of the competition between the Edison/Biograph cartel and the independents such as Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Pictures (IMP) company. Not only did Ramsaye minimize the work of French pioneers the Lumiere brothers, he completely ignored the French Gaumont company and the groundbreaking female filmmaker they employed between 1896 and 1907, Alice Guy-Blache. Solax Studios, the company founded by Blache with husband Herbert Blache after their arrival in the U. S. in 1907, is not mentioned.

In reality, only a half-dozen years before Ramsaye began work on his magnum opus, “Madame Alice Blache” was one of “The Leading Manufacturers and Producers” featured in a July, 1914, special edition of The Moving Picture World, the leading film industry trade publication. Although predictably the lone female executive is asked to opine on the role of women in the nascent industry, Blache makes the case for females being uniquely qualified to be leaders in the art of motion picture production.

“Not only is a woman as well-fitted to stage a photodrama as a man, but in many ways she has a distinct advantage over him because of her very nature and because much of the knowledge called for in the telling of the story and the creation of the stage setting is absolutely within her province as a member of the gentler sex. . . All of the distinctive qualities which she possesses come into direct play during the guiding of the actors in making their character drawings and interpreting the different emotions called for by the story.” The Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914.

But it wasn’t merely her artistic sensibilities that marked her work with Solax. Blache was quick to react when long format “feature” films began to revolutionize the production, distribution and exhibition of motion pictures in America. In 1912, a new production unit, Blache Feature Films, was formed within Solax to make films of three reels or more. Along with her contemporary, Helen Gardner (Cleopatra, 1912), Blache made feature-length films nearly two years before D. W. Griffith’s Judith of Bethulia. Not content to stay put in Fort Lee, New Jersey, Solax sent production units far afield. In early 1914, a Solax crew went to Mexico to film a story about the revolution, only leaving after their lives were threatened when real bullets were fired their way, but continuing to work with U. S. troops in Texas.

“There is nothing connected with the staging of a motion picture that a woman cannot do as easily as a man, and there is no reason why she cannot completely master every technicality of the art.” Alice Guy-Blache, The Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914.

In the same issue of The Moving Picture World, Herbert Blache was prescient enough to foresee that motion pictures could rise to the level of classic works of art, and return great profit to the producer of that art:

” . . . the time is at hand for the serious minded producer of photodramas to choose his subject and stage it with the idea constantly in mind that he is creating something that will not only win the plaudits of the multitudes for a day or a year, but will bear reproduction in the form of renewed prints for many years to come. . . [and] offers possibilities of money profits that are beyond the rosiest dreams of the producers of ordinary motion pictures. Although the time and money required to stage what we might term a ‘picture classic’ is far in excess of that demanded by a less carefully staged production, once created it’s value is really enormous. . . like a painting, who can say that it may not some day be a pearl without price.” The Moving Picture World, July 11, 1914.

Without a doubt, during her active years in the industry, Alice Guy-Blache was recognized as an important figure in motion pictures. In 1912, Louis Reeves Harrison, an early film writer and an early, strong advocate of motion pictures as the most important art form of the 20th century, wrote a lengthy profile of Blache and Solax studios for The Moving Picture World.

“[At Solax,] the head of the business, the originator of it, the capitalist, the art director, the chief working director, is a refined French woman, Madame Alice Blache.

“This is woman’s era, and Madame Blache is helping to prove it without making any fuss at all. . . and she is so modest about what she has done in the Gaumont and Solax companies that I had to depend upon others for any details relating to her remarkable career in the production of moving pictures.

“I learned that Madame Alice Blache became associated with the Gaumont Company very early in the game, when Mr. Gaumont was absorbed with the scientific department of production or merely engaged in photographing moving objects. She inaugurated the presentation of little plays on the screen by that company some sixteen or seventeen years ago, operating the camera, writing or adapting the photodramas, setting the scenes and handling the actors. I had an opportunity to see how efficient she was in her diversity of roles before the day was over and was amazed at her skill, especially in directing the action of a complicated scene.” “Studio Saunterings By Louis Reeves Harrison,” The Moving Picture World, June 15, 1912.

The praises of Louis Reeves Harrison aside, why should we care about or even pause to remember Alice Guy-Blache more than nine decades after she made her last film? Because she is truly unique. She was present at the dawn of motion photography, working as a pioneer in creating the first moving pictures that told stories. She was among the very first who thought of motion photography as a means to tell stories, and tell them in a way that no prior art form could ever do. And she put those thoughts into action and created narrative filmmaking. To put this into perspective chronologically, the beginnings of her film work at Gaumont coincided roughly with the first public projection of motion pictures in France and in New York. Narrative films would not even begin to exceed the other early forms of filmmaking — trick film, news film, documentary film — until 1903-04, and would not become the dominant form of film produced in the United States until 1907-08, more than ten years after Blache made her first story films for Gaumont in 1896.

Coming to the U. S. initially to work for the American branch of Gaumont in New York, within a couple of years she founded her own production company, and built two studios under the Solax name, the first in Flushing, Queens, New York, the second at Fort Lee, New Jersey. She made films through the most tumultuous period in the history of motion pictures — more cataclysmic in terms of careers, companies and wealth created and destroyed between 1912 and 1918 than during the “change” to sound a decade and a half later. Though Solax and her career as a filmmaker did not survive into that later period, her contributions from 1896 to 1920, a period spanning the invention of motion photography and the flowering of film into a form of high art, are unmatched. D. W. Griffith was acting and writing scenarios in 1908; Alice Guy-Blache had already been making movies for a dozen years. No one else was an active, important artist in motion pictures during that entire period, from the 1890s to the rise of “Hollywood.” For that, she deserves to be remembered and honored.

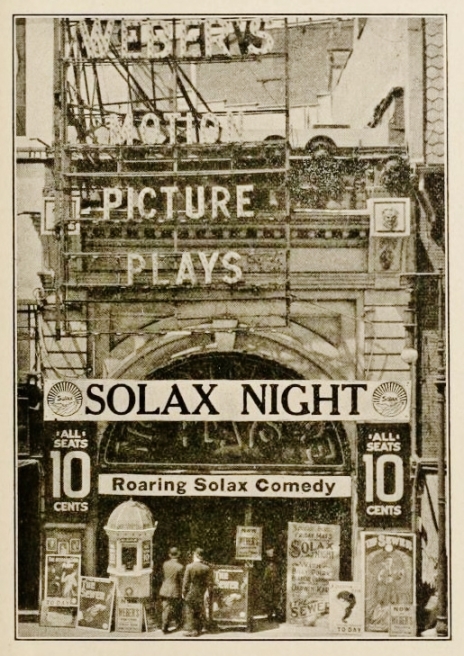

“SOLAX NIGHT on BROADWAY” at the Weber Theatre, May 18, 1912.

“SOLAX NIGHT on BROADWAY” at the Weber Theatre, May 18, 1912.

* * *

Further (and far more detailed) information on Alice Guy-Blache can be found at these sites:

Alice Guy-Blache at Wikipedia.org;

and in case you missed it above, the Be Natural-Kickstarter site.

Hi Gene,

little comment….A nice documentary on this lady was made here in Canada few years ago…at least 7 or more

by a director named MARQUISE LEPAGE…I THINK THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD WAS INVOLVED

I recall seeing a very good documentary on Alice-Guy broadcast in the US by TCM back around 2000. Per IMDb, the LePage film was made in 1995. I’m not sure if it is the same as the one shown on TCM; also LePage was interviewed as part of the new documentary-in-progress, “Be Natural.”

hi gene,

Must be the same one..Marquise is a very rare name so. And it is very possible 1995. It is a good film and a fine resume of the beginning of motion picture.

lise

I thought about it, and it WAS the one shown in 2000, the title in English was something like “The Lost Garden of Alice-Guy Blache,” it was very good, probably over an hour, hour and half long.