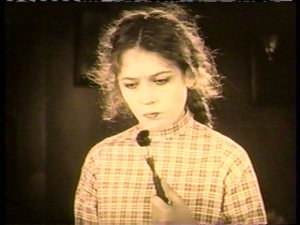

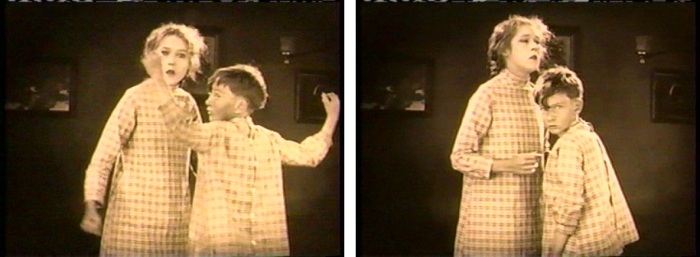

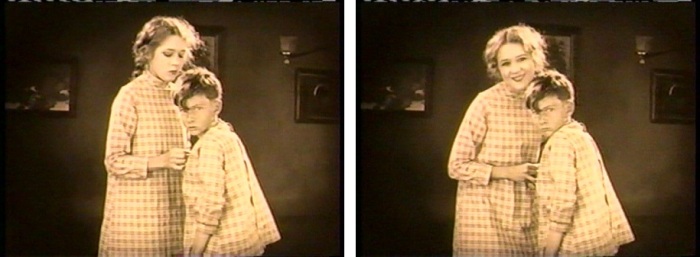

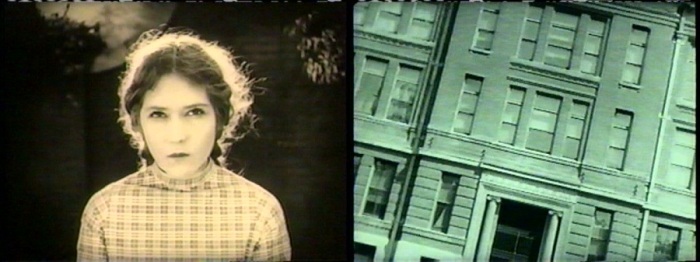

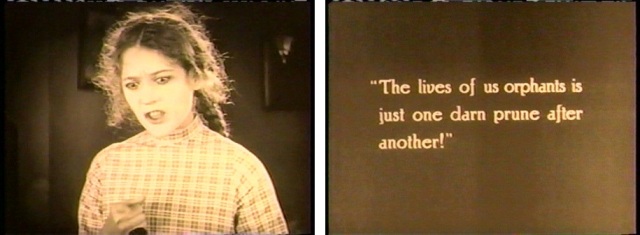

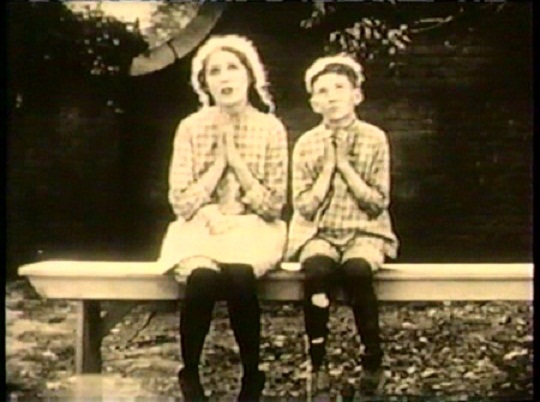

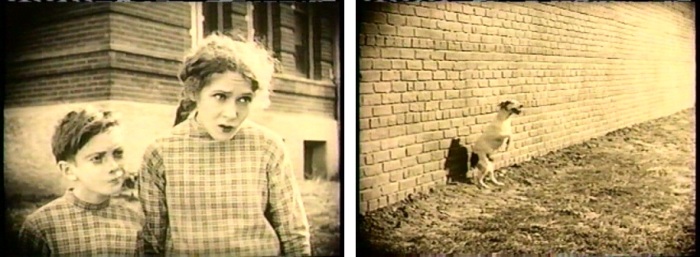

Above: Three Faces of “Judy Abbott” (Mary Pickford): Left, angry; Right, hopeful, Center, stoned. Below: Manna from “heaven” with apple-jack proves a dangerous combination, as buildings appear to be falling in on an intoxicated Judy and her orphan pal. Daddy Long-Legs (Pickford, First National, 1919, directed by Marshall Neilan, adapted by Agnes Johnson from the novel and play by Jean Webster).

Above: Three Faces of “Judy Abbott” (Mary Pickford): Left, angry; Right, hopeful, Center, stoned. Below: Manna from “heaven” with apple-jack proves a dangerous combination, as buildings appear to be falling in on an intoxicated Judy and her orphan pal. Daddy Long-Legs (Pickford, First National, 1919, directed by Marshall Neilan, adapted by Agnes Johnson from the novel and play by Jean Webster).

In previous essays, I’ve described the way the careers of Mary Pickford and Ruth Chatterton occupy opposite sides of what I referred to as the “great divide” in motion picture history, between silence and sound; but also between theater and motion pictures. Pickford, a key figure in the development of motion picture acting, became the first international movie star. Chatterton, the first female star of the sound era, was a contemporary of Pickford’s. But they first attained stardom at the same time: Chatterton became a star on the stage nearly two decades before she made her first film. They occupied parallel worlds of film and theater. Their careers mirrored the other, but they never worked together in either medium, though on occasion they and their work appeared but a few city blocks from each other. They would also share one major work in their respective “canons.”

A rudimentary “timeline” offers some interesting comparisons and contrasts. In the spring and summer of 1909, Pickford, already a ten-year veteran of the stage, made her first films for Griffith at Biograph. That summer, Chatterton was making her first appearances on the professional stage with the Columbia Players in Washington, D.C.

A rudimentary “timeline” offers some interesting comparisons and contrasts. In the spring and summer of 1909, Pickford, already a ten-year veteran of the stage, made her first films for Griffith at Biograph. That summer, Chatterton was making her first appearances on the professional stage with the Columbia Players in Washington, D.C.

Chatterton had her first important lead role and made her Broadway debut in The Great Name in 1911. It was, for Pickford, the year she left Biograph, married Owen Moore and signed with Carl Laemmle’s I.M.P. company and, for the first time as a motion picture actor, she was a star with her name on film credits and in studio publicity. The following year, 1912, Pickford returned to Biograph, after what had been dismal stint with I.M.P. (and Owen Moore), and did some of her best work in short films directed by Griffith — Friends, Female of the Species, and The New York Hat. That same year, Ruth Chatterton received her first national recognition and her first taste of stardom on stage, on Broadway in The Rainbow.

In 1913, as Chatterton toured nationally in The Rainbow, Pickford returned to the stage in David Belasco’s A Good Little Devil, to excellent reviews, but would not remain on stage — she signed with Adolph Zukor and Paramount. The following year Chatterton scaled the peak of theatrical stardom in Chicago and New York, in consecutive runs in those two cities — Daddy Long-Legs played a total of 52 weeks and 470 performances — while Pickford signed the first six figure contract in motion pictures.

In 1913, as Chatterton toured nationally in The Rainbow, Pickford returned to the stage in David Belasco’s A Good Little Devil, to excellent reviews, but would not remain on stage — she signed with Adolph Zukor and Paramount. The following year Chatterton scaled the peak of theatrical stardom in Chicago and New York, in consecutive runs in those two cities — Daddy Long-Legs played a total of 52 weeks and 470 performances — while Pickford signed the first six figure contract in motion pictures.

Well before 1919, Pickford and Charlie Chaplin had become the most recognizable faces on the planet. In that year, she was looking for film projects that allowed her to stretch, but also to remain loyal — and recognizable — to her core fan base, those who loved “Little Mary.” She needed a particularly strong vehicle this time: it was to be her first independent production after the conclusion of her contract with Zukor and Paramount.

She found it: a story that was a near-perfect match, one that met all the necessary criteria, and one that was also familiar to the general public. It was a story that had already been tested and proven a huge success, first as a magazine serial and in book form, then on stage in Jean Webster’s four-act adaptation of her own original story, Daddy Long-Legs. Pickford bought the property, and made it her first project with her own production company, releasing it through First National Pictures (just weeks later, Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Chaplin and D.W. Griffith would create their own distribution company, United Artists).

She found it: a story that was a near-perfect match, one that met all the necessary criteria, and one that was also familiar to the general public. It was a story that had already been tested and proven a huge success, first as a magazine serial and in book form, then on stage in Jean Webster’s four-act adaptation of her own original story, Daddy Long-Legs. Pickford bought the property, and made it her first project with her own production company, releasing it through First National Pictures (just weeks later, Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Chaplin and D.W. Griffith would create their own distribution company, United Artists).

Enough time had passed — five years — since the Jean Webster play made a star of Ruth Chatterton, and millions of movie goers, having never seen Daddy Long-Legs on stage, would not associate it exclusively with a particular actor. But Pickford would take no chances. Successful as the original was, she would not produce a scene-for-scene copy of the play.

As adapted for film by Agnes Johnson, director Marshall Neilan, and producer Mary Pickford, the basic story contained within the four-act play was largely retained. However, the first act would be virtually unrecognizable in the film adaptation. It would serve as a bridge of sorts, where the protagonist, the orphan child Judy Abbott, age eighteen in the play, would revert to a raucous version of America’s Sweetheart, along the lines of her classic performance in the original Tess of the Storm Country (1914), one that has it origins in her “Harum-Scarum” character in the Griffith Biograph short, The Mountaineer’s Honor (1909).

As adapted for film by Agnes Johnson, director Marshall Neilan, and producer Mary Pickford, the basic story contained within the four-act play was largely retained. However, the first act would be virtually unrecognizable in the film adaptation. It would serve as a bridge of sorts, where the protagonist, the orphan child Judy Abbott, age eighteen in the play, would revert to a raucous version of America’s Sweetheart, along the lines of her classic performance in the original Tess of the Storm Country (1914), one that has it origins in her “Harum-Scarum” character in the Griffith Biograph short, The Mountaineer’s Honor (1909).

It was this simple, childlike version of Judy that Pickford chose to begin the film. By contrast, the Judy of Webster’s novel and play is from the outset far too mature and intelligent to remain at the orphanage (she attended and graduated from the local high school while living at the orphans’ asylum), hence the decision of one of the trustees of the institution to fund her college education. In Pickford’s version, this change from wild child to college-ready youthful maturity is made rather abruptly — it takes three reels (or about 35 minutes into the film) before we see the transition to an emotionally (but not intellectually) mature Judy Abbott. There is very little about her to indicate why anyone, especially a stranger, would pay to send this uneducated girl to any institution of higher learning. That doesn’t mean the finished film was anything less than great comedy.

Although in the film version, Pickford takes her comedy further into the realm of slapstick and knockabout farce than she had ever done before, she does so in way that showcases the depth of her acting ability, effortlessly sliding from buffoonery to pathos almost from frame-to-frame. I’ve selected two sequences from the first third (the first two reels) of the film, which are actually one long extended sequence divided into two discrete parts.

First, the sequence that is essentially our introduction to Pickford’s “Judy Abbott,” the “Great Prune Strike” scene; then the remarkable “drunk” sequence, in which Judy and another orphan child become inadvertently intoxicated. It is a concept that could not be realized in motion pictures or television today, one that is too far outside the self-inflicted parameters of puritanical correctness of our society today.

Mary Pickford’s Judy Abbott is a little Lenin, fighting for the downtrodden orphans who are used the same way that the orphan asylum’s founder, a prison warden, used his prisoners as slave labor (a bit of background that is nowhere to be found in any of Jean Webster’s versions of the story). I’ve also chosen (for the sake of space) not to include the bit of business where the intoxicated orphans accidentally knock the Matron’s assistant, “Pansy Gumph,” into the water well (Pansy is another creation of the film adaptation and appears nowhere in the original book or play).

The Matron, Mrs.Lippett and her “right hand,” Pansy Gumph investigate the commotion,

The Matron, Mrs.Lippett and her “right hand,” Pansy Gumph investigate the commotion, . . . the orphans’ bravado instantly disappears.

. . . the orphans’ bravado instantly disappears.

Their punishment? No supper.

Their punishment? No supper.

“PLEASE, MR. GOD, WE WANT FOOD.” The way of the Lord is mysterious indeed. He comes in the form of a thief disposing unwanted loot — sandwiches and hard cider.

The way of the Lord is mysterious indeed. He comes in the form of a thief disposing unwanted loot — sandwiches and hard cider.

“I DIDN’T KNOW HE WAS SO CLOSE.”

What’s the Matter with That Building Over There?

What’s the Matter with That Building Over There? ” WHICH ONE ???”

” WHICH ONE ???”

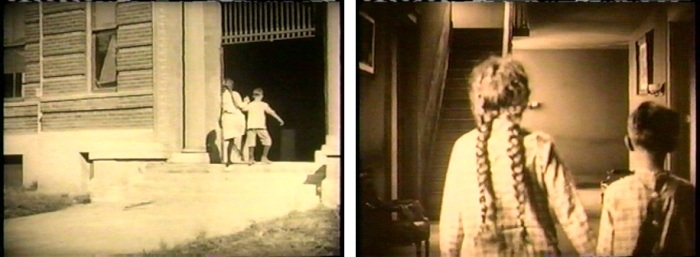

“Let’s Go In Before Everything Falls In on Us!”

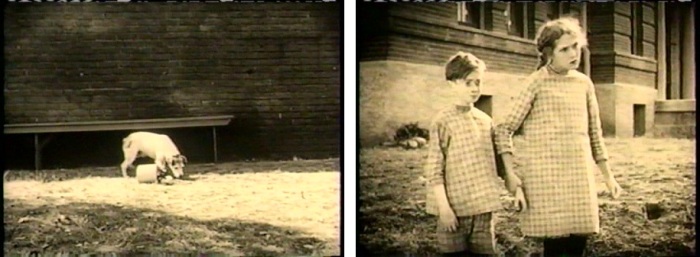

But the orphans leave behind just enough apple-jack to tempt a stray creature . . .

But the orphans leave behind just enough apple-jack to tempt a stray creature . . .

And now, back to the “safety” of the orphans’ asylum.

And now, back to the “safety” of the orphans’ asylum.

The remainder of the film stays relatively close to Jean Webster’s original. Webster died shortly after giving birth to her first child, in June 1916, just weeks after her play, Daddy Long-Legs, completed a third season and second national tour. She also did not live to see the play performed to a packed theater night after night in London to war-weary audiences in the summer of 1916. One also wonders what she would have thought of Mary Pickford’s highly successful screen adaptation of her story. Unfortunately we’ll never know. But a renewed interest in Pickford’s work has, in a way almost ironic, given extended life and new audiences for Webster’s story a century after its creation.

One thought on “MARY PICKFORD’S “Daddy Long-Legs””