” . . . The picture is finely acted by Dorothy Mackaill, who comes as close to Lillian Gish’s methods of expression without giving an imitation of them as anyone we can mention. She is always sincere, unaffected and convincing. D. W. will get this girl yet.” Review of Mighty Lak a Rose, Motion Picture Magazine, May 1923.

Looking very much like Lillian Gish gone bad: “Another personality to be reckoned with . . . Dorothy Mackaill. She has just finished playing opposite Richard Barthelmess in ‘The Fighting Blade,’ and her portrayal has interested all those who have seen it. She promises even greater things when her screen technique is perfected.” Motion Picture Magazine, October, 1923

Looking very much like Lillian Gish gone bad: “Another personality to be reckoned with . . . Dorothy Mackaill. She has just finished playing opposite Richard Barthelmess in ‘The Fighting Blade,’ and her portrayal has interested all those who have seen it. She promises even greater things when her screen technique is perfected.” Motion Picture Magazine, October, 1923

One of the most notable beneficiaries of the renewed interest in classic “Hollywood” film, Dorothy Mackaill is now regarded by modern audiences as one of the leading stars of the “pre-Code” era, where relaxed enforcement of production code standards led to films that regularly explored honest, adult themes that resonate with 21st century viewers. With a persona embellished by Complicated Women, the documentary study of pre-code actresses, and further defined and burnished by her roles in films like The Office Wife and, especially, Safe in Hell, Mackaill has emerged from being a dark horse (or more pointedly, a dark blonde) to one of the most compelling figures of the period.

But as is often true in an evaluation of the popular arts, particularly film, the picture is skewed by the availability of the material to be studied. In Mackaill’s case, most of the films screened, broadcast or available for home video are sound films, those of pre-code Hollywood, especially those from Warner Brothers/First National and RKO, the rights to which were acquired by Turner Entertainment in the late 1970s and broadcast since the late 80s by Turner’s TNT and (beginning in the mid 90s) TCM. Although Mackaill made roughly eighteen “all-talking” pictures from 1929 to 1934 — the pre-Code era — and another half dozen “part-talkies” and “sound” effects films in 1928, the bulk of her career was in silent film.

In more than forty films, nearly all features, from 1920 to 1928, Mackaill evolved from Ziegfeld dancer to comic foil to ingénue to featured player to full-fledged film star with First National Pictures. Though never quite reaching the heights of several of her mid 1920s colleagues at First National — Colleen Moore, Norma and Constance Talmadge — she was highly regarded within the industry as a versatile performer, a popular star whose sexy “everywoman” persona preceded Joan Crawford, and as an actress with equal appeal to male and female audiences.

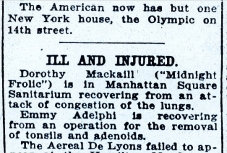

Mackaill got an early break in American show business with Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr. in his “Midnight Frolic,” the song-dance-comedy-girly revue staged originally at the small rooftop cabaret/auditorium of the Ambassador Theatre on West 49th Street at Broadway.

The Midnight Frolic was not an offshoot of the Follies, but rather an attempt to capitalize and extend the concept of the nightclub/cabaret craze where patrons paid an admission to enter a full service entertainment establishment where one could eat, drink (food and drink tabs separate from the admission or “cover” charge, of course), dance, and see performances — typically solo or partner acts. Ziegfeld injected the musical-comedy “revue” into the concept as the entertainment in place of or in addition to the solo acts, with a show lasting a little over an hour (eventually growing to more than ninety minutes as the shows became more elaborate over the years), including a twenty-minute intermission between acts during which time the patrons had use of the floor and could dance to the orchestra until the second “act” appeared.

The Midnight Frolic was not an offshoot of the Follies, but rather an attempt to capitalize and extend the concept of the nightclub/cabaret craze where patrons paid an admission to enter a full service entertainment establishment where one could eat, drink (food and drink tabs separate from the admission or “cover” charge, of course), dance, and see performances — typically solo or partner acts. Ziegfeld injected the musical-comedy “revue” into the concept as the entertainment in place of or in addition to the solo acts, with a show lasting a little over an hour (eventually growing to more than ninety minutes as the shows became more elaborate over the years), including a twenty-minute intermission between acts during which time the patrons had use of the floor and could dance to the orchestra until the second “act” appeared.

Like most of the showgirls appearing with Ziegfeld, particularly those in the “Frolic” which stayed in New York rather than touring as did the “Follies,” Mackaill by necessity held down more than one gig at a time.  She could do the midnight shows with Ziegfeld, then also appear in the live shows that were worked in with movies at the many venues along Broadway. Not surprisingly, she also wound up in the movies themselves beginning as a pretty comic foil to film comedian Johnny Hines in several of his “Torchy” comedy shorts for Hines’ independent production company, Mastodon Films, based in New York, Mackaill’s “back yard” during 1920-22. In addition to Mackaill, Hines was credited with (or rather, credited himself with) “discovering” for the movies Norma Shearer, Billie Dove, Doris Kenyon, Jacqueline Logan and Jobyna Ralston.

She could do the midnight shows with Ziegfeld, then also appear in the live shows that were worked in with movies at the many venues along Broadway. Not surprisingly, she also wound up in the movies themselves beginning as a pretty comic foil to film comedian Johnny Hines in several of his “Torchy” comedy shorts for Hines’ independent production company, Mastodon Films, based in New York, Mackaill’s “back yard” during 1920-22. In addition to Mackaill, Hines was credited with (or rather, credited himself with) “discovering” for the movies Norma Shearer, Billie Dove, Doris Kenyon, Jacqueline Logan and Jobyna Ralston.

Mackaill also had the good fortune to work with one of the more highly regarded directors of the 1920s, John S. Robertson, in several films beginning with The Fighting Blade in 1923. Produced by Robertson’s Inspiration Pictures, distributed through Associated First National, The Fighting Blade cast Mackaill with a major star of the period, Richard Barthelmess, who had first caught the attention of critics and film-goers as the “Chinaman” in D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms in 1919, opposite Lillian Gish. Robertson, though forgotten by modern audiences and neglected by historians, began as an actor/director with Vitagraph in 1916, and went on to direct more than 50 features spanning the silent and early sound periods, working primarily as a contract director with Paramount, First National and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, then in the mid 1930s for Universal and RKO.

Robertson was particularly good at drawing effective performances from an astonishing number of female leads. In addition to his three films with Dorothy Mackaill, among those stars were Alice Terry, Corinne Griffith, Alice Brady, Billie Burke, Marguerite Clark, Dorothy Gish, Mary Astor, May McAvoy, Bessie Love, Lillian Gish, and Greta Garbo; and in addition to his eight films with Richard Barthelmess, he directed important male stars such as John Barrymore, John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, Nils Asther and William Powell. Robertson retired in 1935 after directing his final picture, Our Little Girl, starring the biggest box-office draw of the period, Shirley Temple. Naturally, he is best known for those films that have survived and been restored, rescreened and reissued on home video, such as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1921), Captain Salvation (1923) and most of his MGM work that, thanks to TCM, gets a fairly regular airing for television. But perhaps the best tribute to his ability was his selection by Mary Pickford to direct the only film she ever re-made, Tess of the Storm Country, in 1922.

Dorothy Mackaill with Richard Barthelmess, promoting “Twenty-One” (1923, Associated First National, directed by John S. Robertson), from Motion Picture Magazine, January 1924

Dorothy Mackaill with Richard Barthelmess, promoting “Twenty-One” (1923, Associated First National, directed by John S. Robertson), from Motion Picture Magazine, January 1924

“You cannot produce Mary Pickfords, or Charlie Chaplins or Douglas Fairbankses or Dick Barthelmesses in a short time. Every great actor or actress has worked for success — a long, hard time of it most of them have had, too. . . On the other hand, I think a girl like Dorothy Mackaill a clever little actress who with proper training will some day make a real star.” John S. Robertson, “Is the Life of a Star Only Three Years?” Motion Picture Magazine, October 1923.

By 1924, the movies and the concept of movie stardom had existed long enough to allow for a consideration of a passing-of-the-torch to a “younger generation” of performers who, naturally, invited comparison to the pioneering figures of what seemed to observers of the time as a rapidly maturing art form and profession. In an essay for Motion Picture Magazine in January, 1924 , film writer Gladys Hall asked, “What Have They to Give Us?”

“Do you realize that this is the first time in the genealogy of Motion Pictures that there has been a Younger Generation to expect anything from? . . . What can we expect from the Younger Generation? They eschew emulation . . . they don’t want to be second Mary Pickfords or second to anyone at all. They stake their own claims . . .”

“The ‘Infant Industry’ has become mature . . . the Screen has become a Parent. The parent of such younglings as Mary Astor, Dorothy Mackaill, Glenn Hunger, Clara Bow, Eleanor Boardman, Pauline Garon, Ramon Novarro, and such like. What are they going to do? What have they to give us?”

Dorothy Mackaill, from “What Do They Have to Give Us?” by Gladys Hall, Motion Picture Magazine, January 1924.

Dorothy Mackaill, from “What Do They Have to Give Us?” by Gladys Hall, Motion Picture Magazine, January 1924.

“Dorothy [Mackaill] brings Sureness to the Screen. Sureness of herself. She came to America a screen ‘greenhorn’ from England. She didn’t know D. W. Griffith from plain John Smith. She didn’t know Flo Ziegfeld from Bill Sunday. She went straight to the aforesaid Ziegfeld and got a job. And from [Ziegfeld’s] ‘Midnight Frolic’ she was observed by [Mary Pickford director] Mickey Neilan who transposed her from the footlights to the Kliegs in [the 1921 film] Bits of Life.

“‘It happened’ said Dorothy, ‘because I was full of pep and nerve and not afraid of God, man nor beast. Prettiness . . . oh, gosh! But there are lots and lots of pretty girls. . . It wasn’t because I was pretty. It was just because I wasn’t afraid. I hadn’t had time to develop any self-consciousness about Personages and what they or could not do for me. I hadn’t had time to have the self-confidence I came with taken away from me. . . I haven’t decided — I haven’t decided, mind you — what I can do best. I don’t know yet. In the meantime, I want experience in the best parts I can get, with the right to pick and choose.’ No ‘what do you think of this’ or ‘shall I ask about that?’ from Dorothy. Child of her age, she makes her own decisions and runs her own car.” “What Have They to Give Us?” By Gladys Hall, Motion Picture Magazine, January 1924.

“Dorothy is going right ahead and proving that all the extravagant things said about her screen presence and her acting ability are the truth … the whole truth … and nothing but the truth. She is, without any doubt, one of the most interesting personalities that has come to the screen in many a month.” Motion Picture Magazine, May 1924.

Dorothy Mackaill by Edwin Bower Hesser, Motion Picture Magazine, May 1924.

Dorothy Mackaill by Edwin Bower Hesser, Motion Picture Magazine, May 1924.

“When an actress can move a hard-boiled studio audience to a deep appreciation of her work before the camera she is some actress. That is what Dorothy Mackaill can do. Her work in “The Man Who Came Back” stamps her as a coming artist of the screen.” Photoplay Magazine, November 1924.

Mackaill in the 1924 Photoplay Magazine compilation volume, “Stars of the Photoplay.”

“DOROTHY MACKAILL began her professional career as a dancing teacher, at the age of ten, in her father’s dancing academy at Hull, England. At sixteen she was leader of two numbers in ‘Joybells’ at the London Hippodrome, and at seventeen a beauty with the Ziegfeld ‘Follies.’ During her early screen career in this country she played in ‘Torchy’ comedies, in ‘The Lotus Eaters,’ with John Barrymore and in ‘Mighty Lak’ a Rose.’ Born in Hull, England, in 1903, and educated there and in London. Has blonde hair and hazel eyes, weighs 121 pounds, and is five feet, four inches tall. Unmarried.” Stars of the Photoplay (1924, Photoplay Magazine).